🏜️ Bison, Bluffs, and Belly Laughs: Saydie and I Take on the Badlands

Our Great Southwest Adventure took a wild turn when Saydie and I rolled into South Dakota’s Badlands—land of jagged peaks, fossil beds, and the kind of wind that makes your hair look like you lost a fight with a tumbleweed. We’d been camping for weeks, living off trail mix and questionable gas station burritos, and the Badlands felt like nature’s dramatic encore.

As we pulled into the park, Saydie looked out at the landscape and said, “It looks like Mars had a mood swing.” She wasn’t wrong. The terrain is otherworldly—sharp ridges, striped rock layers, and valleys that seem to whisper ancient secrets. But beneath the beauty lies a deep and complex history.

📜 The Land Before Roads

The Badlands, or Mako Sica in Lakota (meaning “land bad”), have been home to Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Archeological finds show that early tribes hunted mammoths and bison here as far back as 7,000 years ago. By the 1700s, the Oglala and Brule bands of the Teton Sioux had settled in the region, adapting to the harsh plains after migrating from timbered lands.

The land was sacred, a place of hunting, gathering, and spiritual connection. But with westward expansion came treaties, broken promises, and displacement. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 handed the land from France to Spain, then back to France, and finally to the United States in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase. What followed was a painful reshaping of Native life, as tribes were pushed onto reservations and their ancestral lands carved into national parks and monuments.

Today, the Badlands National Park shares borders with the Pine Ridge Reservation, home to the Oglala Lakota Nation. The reservation is rich in culture and resilience, and efforts are ongoing to ensure Native history is honored and integrated into the park’s story.

😂 Saydie vs. The Badlands

Now, back to the comedy. Saydie, armed with binoculars and a junior ranger badge she earned at a previous stop (after interrogating a ranger about prairie dog diets), was on a mission: spot a bison, name it, and declare it her spirit animal. We saw one within ten minutes. She named it “Gerald” and insisted he winked at her.

We hiked the Notch Trail, which includes a log ladder that looks like it was built by someone with a grudge against knees. Saydie, of course, scampered up like a mountain goat while I climbed like a dad who forgot he’s not 25 anymore. At the top, she declared, “This view is worth the trauma,” and I couldn’t argue.

Later, we visited the Fossil Exhibit Trail, where Saydie tried to convince a group of tourists that she discovered a new species of ancient lizard. She named it “Saydisaurus Rex” and gave it a backstory involving dance battles and glitter.

🌄 Reflections in the Dust

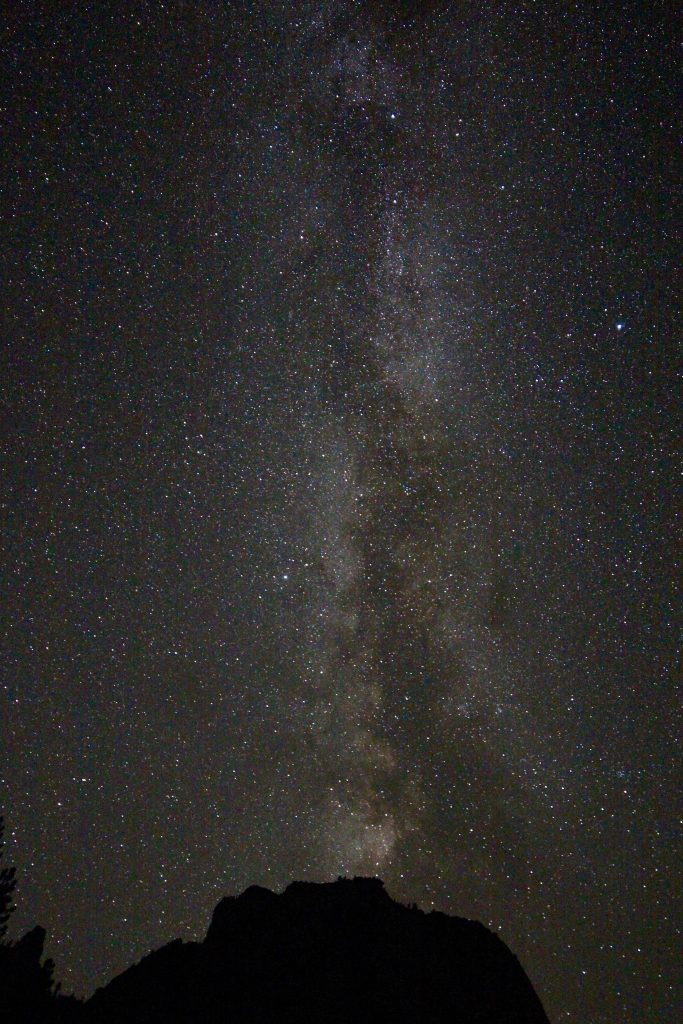

As the sun dipped behind the spires, casting long shadows across the prairie, we sat on a bluff and watched the sky turn to fire. Saydie leaned against me and said, “I didn’t know history could be so cool and so sad at the same time.” That’s the Badlands for you—a place of breathtaking beauty and deep scars, laughter and legacy.

We left dusty, sunburned, and full of stories. The Badlands had given us more than just views—it gave us connection. To the land, to its people, and to each other.

Next stop: somewhere with fewer ladders and more ice cream. But the Badlands? They’ll stay with us forever.