“Where Stone Walls Meet Wild Horizons”

Scotland has always been a land of edges — jagged mountains, restless seas, and winds that carry stories older than memory. Among these landscapes, a curious tradition thrives: the bothy. These simple shelters, scattered across the Highlands and islands, are free to use, open to all, and steeped in the spirit of adventure.

On the Isle of Skye, where the Cuillin peaks pierce the clouds and sea cliffs tumble into the Atlantic, bothies are more than huts. They are gateways to solitude, camaraderie, and the raw pulse of nature. My journey takes me to the Lookout Bothy at Rubha Hunish, perched at the northernmost tip of Skye, where land dissolves into ocean. Along the way, I’ll explore the culture of bothies and the remarkable law that makes such journeys possible: Scotland’s freedom to roam.

“The Humble Hut with a Hero’s Heart”

Bothies are not glamorous. They are not hotels, nor even hostels. They are stone walls, wooden beams, and sometimes a fireplace if you’re lucky. Yet within their simplicity lies their magic.

Once shepherd huts, estate outbuildings, or coastguard stations, many were abandoned until the Mountain Bothies Association began restoring them in the 1960s. Today, over a hundred dot the map of Scotland, each unlocked, each free, each waiting for weary walkers.

The culture of bothying is built on trust. You arrive, perhaps soaked by rain or chilled by wind, and find shelter. You share space with strangers, swap stories, or sit in silence. You leave no trace, except maybe a note in the bothy book — a diary of wanderers who came before.

Luxury bothies exist too, marketed as cozy retreats with hot tubs and Wi-Fi. But the true spirit of the bothy is in its austerity. It is the hut that asks nothing of you except respect, and in return, it gives you the gift of belonging to the land.

“To the Edge of the World – Rubha Hunish”

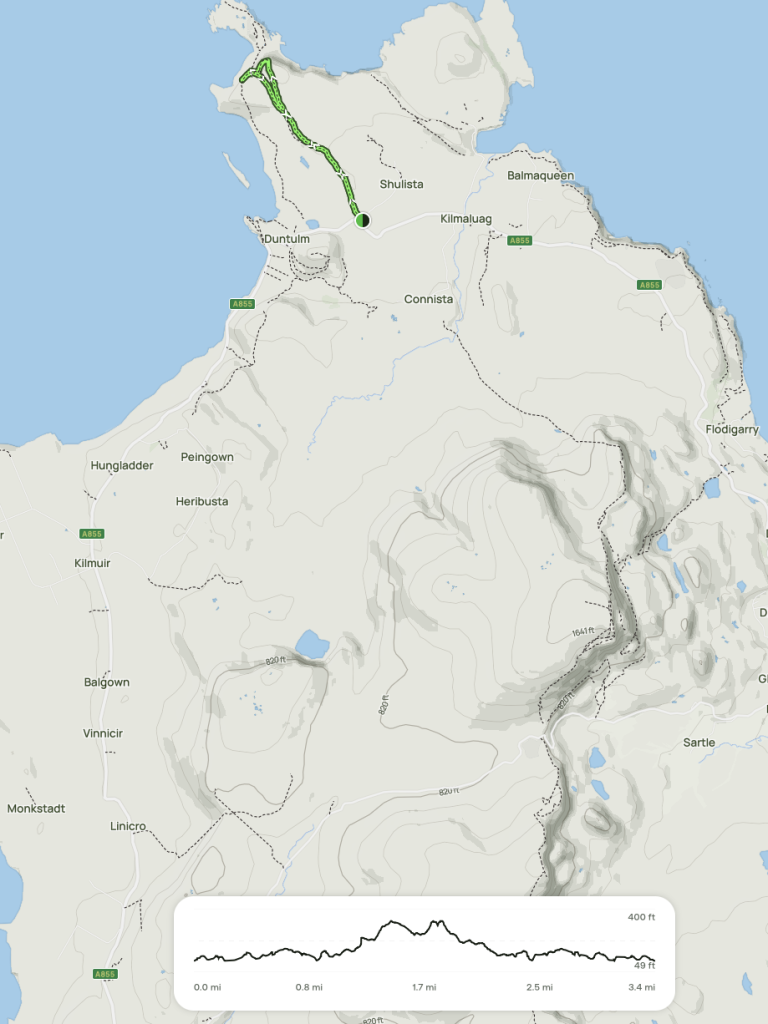

The journey to the Lookout Bothy begins in Shulista, a small crofting village marked by a red phone box. From here, a rough trail winds across moorland, dips through boggy ground, and climbs toward the cliffs of the Trotternish Peninsula.

The hike is not long — about six kilometers — but it demands care. Paths are uneven, weather shifts quickly, and the cliffs are sheer. Yet every step is rewarded with views that stretch across the Minch to the Outer Hebrides.

At last, the bothy appears: a squat, whitewashed hut clinging to the cliff edge. Built in 1928 as a coastguard lookout, it now serves as a shelter for walkers. Inside, it is small — room for three at most. There is no fireplace, no running water, no electricity. But there are binoculars, charts of whales and seabirds, and a bay window that frames the Atlantic like a living painting.

Here, you might sit alone, listening to the crash of waves and the cries of seabirds. Or you might share the space with fellow travelers, swapping tales of hikes and storms. Either way, the bothy offers something rare: the feeling of being at the edge of the world, yet utterly at home.

“The Law of the Land – Freedom to Roam”

What makes bothies possible is not just tradition, but law. Scotland’s Land Reform Act of 2003 enshrined the right of responsible access to most land and inland water. This is often called the freedom to roam.

Unlike in many countries, where private estates block walkers, Scotland invites you in — provided you respect the land, wildlife, and people who live there. You can hike across moors, camp wild, paddle rivers, and yes, stay in bothies.

The Scottish Outdoor Access Code guides this freedom: leave no litter, keep dogs under control, respect privacy, and avoid damaging crops or livestock. It is a balance of liberty and responsibility, a social contract between wanderer and landowner.

This law is more than practical. It is cultural. It says that Scotland belongs to everyone, not just those who own it. It keeps alive the spirit of exploration, ensuring that places like Rubha Hunish remain open to all who seek them.

“Packing for the Wild – A Traveler’s Guide”

If you plan to visit Skye’s bothies, preparation is key. Bring:

- A sleeping bag and mat — there are no beds.

- A stove and fuel — fireplaces are rare, and wood scarcer still.

- Food and water purification — streams are plentiful, but not always safe.

- Maps and a compass — GPS can fail in remote areas.

- Respect — for the land, the bothy, and those who share it.

The best seasons are late spring to early autumn, when daylight lingers and storms are less fierce. Yet even in summer, Skye’s weather can turn in minutes. Always check forecasts, and never underestimate the terrain.

Other bothies on Skye include Camasunary, nestled in a bay beneath the Cuillin, and Ollisdal, remote on the north coast. Each offers its own flavor of wildness.

“Shelter, Sea, and Shared Stories”

Standing in the Lookout Bothy, gazing across the Minch, you understand why bothies endure. They are not conveniences, but experiences. They strip away luxury and leave you with what matters: shelter, landscape, and human connection.

Scotland’s freedom to roam ensures that these experiences remain open to all. It is a law that embodies generosity, trust, and respect — values as enduring as the stone walls of the bothies themselves.

So pack your bag, lace your boots, and head north. The Isle of Skye awaits, with cliffs that fall into the sea, winds that carry ancient songs, and a little hut at Rubha Hunish where you can sit, watch the horizon, and feel utterly free.