Arrival in Luss

The morning began in Luss, a village that feels suspended between past and present. As I stepped out onto its cobbled lanes, I was immediately struck by the sense of timelessness. Stone cottages lined the streets, their walls softened by ivy and their gardens spilling color into the crisp air. The scent of peat smoke drifted from chimneys, mingling with the freshness of the loch.

Luss has roots stretching back centuries. Once a settlement for early Christian missionaries, it later became a hub for crofters and fishermen. Walking its narrow lanes, I felt the weight of that history pressing gently against the present. The parish church, with its quiet graveyard, whispered of generations who had lived and died here, their stories etched into stone.

Tourists milled about, but the village retained its calm dignity. Children played near the pier, their laughter mingling with the cries of gulls. I paused to watch boats bobbing gently, their reflections shimmering in the loch. The rhythm of life here seemed slower, more deliberate, as though time itself had agreed to linger.

I ducked into a café for breakfast—fresh bread, sharp cheese, and a steaming pot of tea. The food was simple, but the setting made it extraordinary. Through the window, I watched the loch shift from silver to slate as clouds drifted overhead. I felt anticipation building, a quiet thrill that today’s journey would carry me beyond the picturesque into something profoundly personal.

Crossing Loch Lomond

The water taxi arrived with a hum, and soon I was skimming across Loch Lomond. The loch stretched vast and restless, its moods changing with every gust of wind. One moment it was a mirror, reflecting the sky in perfect stillness; the next, it rippled with energy, as though stirred by unseen hands.

We passed Inchmoan, its sandy shores pale against the dark water. Known as the “island of the monks,” it seemed to carry a quiet sanctity. Then came Inchfad, rugged and quiet, its shoreline fringed with reeds. Each island felt like a secret, a story waiting to be told.

The mountains loomed beyond, their slopes fading into mist. I felt small in the vastness, yet deeply connected, as though the water carried not just me but generations of memory.

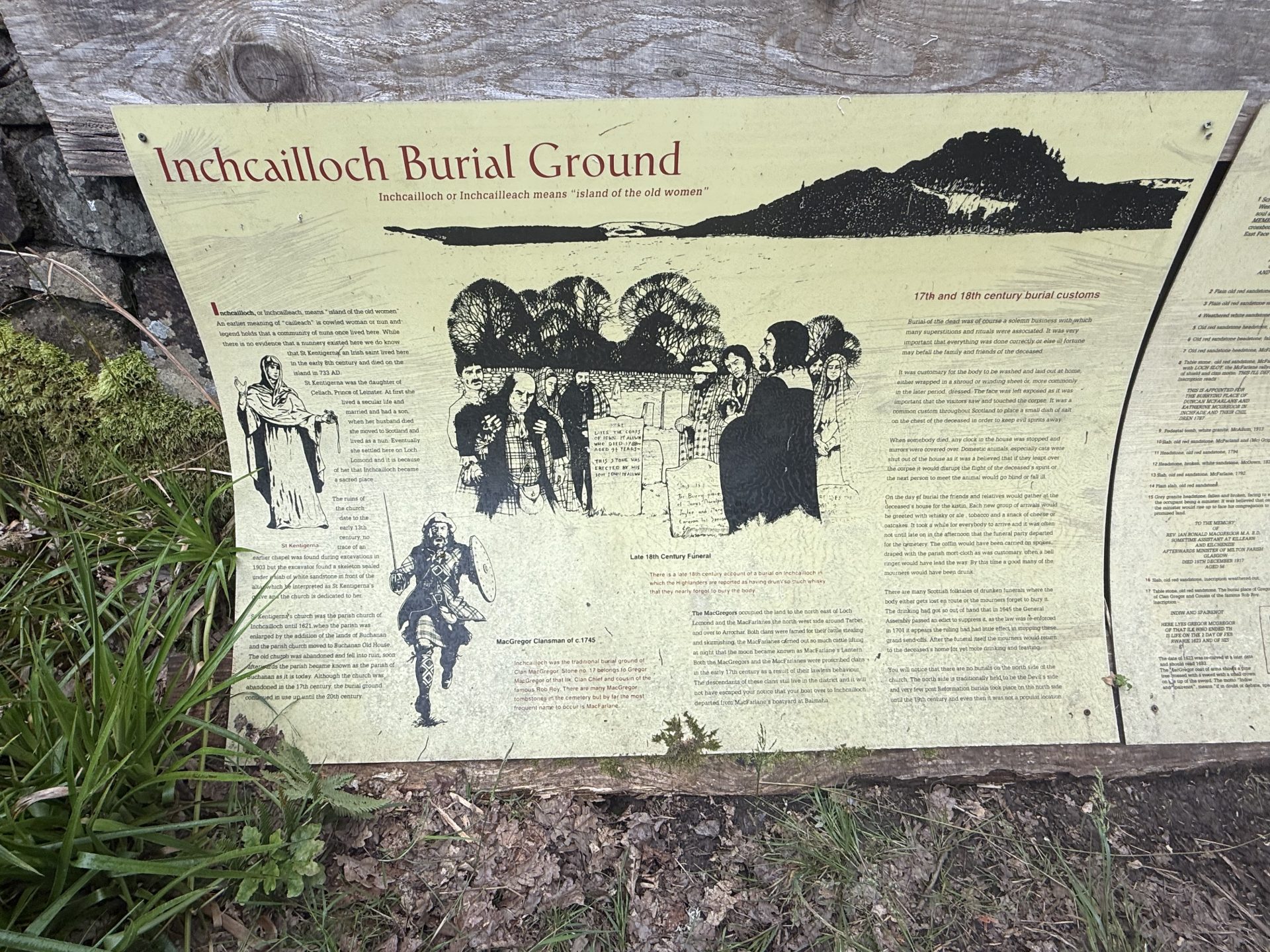

Inchcailloch: Stepping Back in Time

When I stepped onto Inchcailloch, the air seemed to change. The chatter of the loch faded, replaced by the hush of leaves stirring overhead and the distant call of birds. As I left the dock and climbed into the trees, I felt as though I had crossed a threshold. Inchcailloch was not just another island—it was a place where the present thinned, and the past pressed close.

The woodland path wound upward beneath oak and ash, the ground soft with moss and fallen leaves. The earthy scent of damp soil mingled with the sweetness of wildflowers. Light fractured through branches, dappling the trail in shifting patterns. With each step, I felt myself slipping further away from the modern world.

Wildlife stirred around me. A red squirrel darted across the path, its tail a fiery plume. Birds flitted through the canopy—robins, warblers, and the occasional crow whose caw echoed like a warning from another age. The silence was not empty but alive, filled with the subtle movements of creatures who had made this island their home.

I imagined my ancestors walking here centuries ago, their footsteps crunching on the same soil. I pictured Mary MacGregor, my 7th Great Grandmother, moving through glens not far from here in the late 1600s, when her clan lived under proscription. The hardships of that era seemed to echo in the stillness around me. It was easy to picture figures from the past stepping out from behind the trees, their lives woven into the land.

By the time I reached the summit, I felt as though I had crossed into another world. Inchcailloch was no longer just an island—it was a living archive, a place where the past pressed close enough to touch.

The Old Cemetery and the MacGregor Chief

At the summit, the old cemetery revealed itself—weathered stones leaning at angles, inscriptions softened by centuries of rain and wind. I stood before the Greystone, tied to my own lineage, and thought of Mary. She had lived through hardship, her clan forced into hiding, yet she endured.

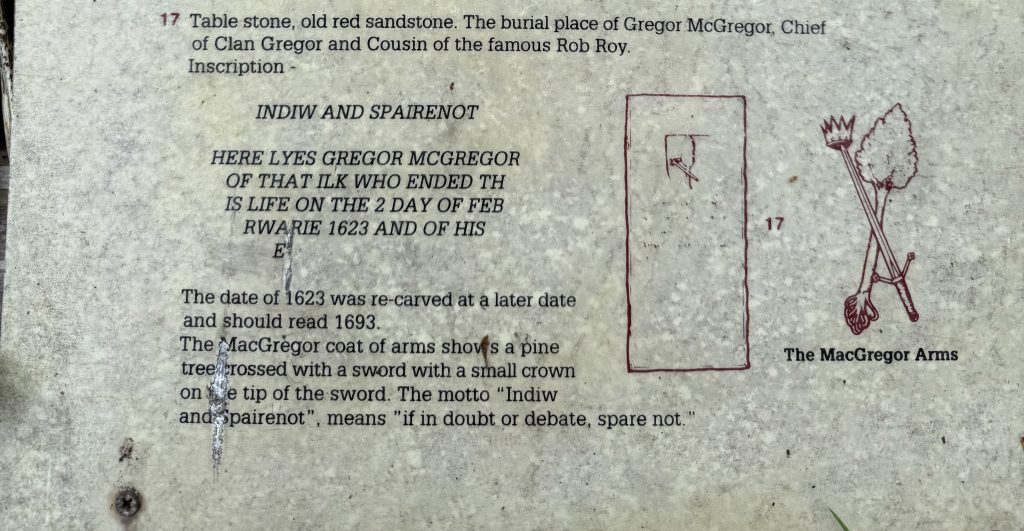

Among the graves here lies a MacGregor clan chief, the uncle of Rob Roy MacGregor. His presence in this burial ground deepens the island’s significance. Rob Roy himself is buried elsewhere, in Balquhidder, but his uncle’s grave here ties Inchcailloch directly to the legendary outlaw’s story.

This chief had guided the clan through troubled times, when their name was forbidden and their lands seized. His leadership was a beacon of resilience, a reminder that even in the darkest days, the MacGregors refused to vanish. To stand before his grave was to stand in the presence of defiance, of a legacy that endured against all odds.

The connection to Rob Roy was palpable. Though separated by generations, the chief’s influence shaped the world into which Rob Roy was born. Rob Roy’s legend—his cattle dealings, his defiance of authority, his transformation into a folk hero—was built on the foundation laid by those who came before him. Inchcailloch held that foundation in its soil.

Clan MacGregor: Survival Under Proscription

The story of the MacGregors is one of resilience against relentless persecution. In 1603, King James VI issued the proscription acts, outlawing the very name MacGregor. To bear it was to invite punishment, even death. Lands were seized, families scattered, and the clan was forced into hiding. For over a century, the MacGregors lived under this shadow, their identity forbidden yet never forgotten.

Survival meant adaptation. Many MacGregors adopted other surnames—Campbell, Murray, Drummond—names that offered protection in a hostile world. Yet beneath those borrowed identities, they remained MacGregors at heart. In whispered conversations, in the songs sung by firesides, in the stories passed down to children, the clan’s spirit endured.

There are tales of families who, stripped of land and livelihood, turned to cattle droving across the Highlands. It was dangerous work, but it gave them mobility and a way to sustain themselves. Others became skilled fighters, offering their swords to neighboring clans or to whichever cause promised survival. Their reputation for toughness grew, and even those who sought to erase their name could not deny their strength.

One anecdote tells of MacGregors who, forbidden to gather under their own banner, would meet in secret glens at night. There, by the light of the moon, they reaffirmed their kinship, swearing loyalty to one another despite the risks. These clandestine gatherings kept the clan alive, binding them together when the world sought to scatter them.

The proscription acts also forced ingenuity. Some MacGregors became renowned for their knowledge of the land—guides who could lead travelers safely through treacherous terrain, or hunters who could provide food when others starved. Their ability to endure in the harshest conditions became legendary.

Mary MacGregor lived through this era. I imagine her childhood shaped by fear and resilience, her family navigating the constant threat of discovery. Yet she survived, and so did her descendants. Her story is part of this larger tapestry of endurance, a testament to the clan’s refusal to vanish.

Reflection: Carrying the Past Forward

As I stood among the stones on Inchcailloch, I felt the weight of these stories pressing close. The proscription acts were meant to erase the MacGregors, yet here I was centuries later, speaking their names freely. The graves were not just markers of the past—they were symbols of endurance, of a clan that refused to be silenced.

I thought of Mary, of Rob Roy, of the chief buried here. Their lives were shaped by hardship, yet they carried forward a legacy that reached me across centuries. To walk on Inchcailloch was to walk alongside them, to feel their presence in the rustle of leaves and the silence of the glen.

Travel often brings us to beautiful places, but this journey was more than that. It was a pilgrimage, a reminder that the past is never truly gone. It lives in the land, in the names, in the stories we carry forward. Inchcailloch gave me not just a glimpse of history, but a sense of belonging—a connection to resilience, to defiance, to survival.

Walking back down the path, I felt reverence in every step. The island had shown me that travel is not only about places—it is about connections, about carrying the weight of ancestry into the present. Inchcailloch was a pilgrimage, a journey through time, and a reminder that I am part of a story that began long before me and will continue long after.