Calanais / Callanish: Walking the Stone Heartbeat of Lewis

There are places where time feels stacked rather than linear—where the past is not behind you but standing all around, watching, listening. The Calanais (Callanish) Standing Stones on the Isle of Lewis are one of those places. Set on a low ridge above loch water that glints and darkens with the weather, these pale, banded monoliths rise from a treeless moor like vertebrae in the earth’s back, turning the sky itself into part of the architecture. People speak about Calanais in terms of mystery, astronomy, ritual and myth; all of those belong here, yet none completely explains why this arrangement of stones continues to feel immediate, almost intimate, five thousand years after it was made. Calanais is not just a monument you look at. It is a space you move through—a choreography designed in rock.

The Land That Gave the Stones

Long before anyone raised a single monolith, the island had written its geology in extravagant time. The stones at Calanais are fashioned from Lewisian gneiss, among the oldest rocks in Europe. Their pale greys and creams streaked with darker minerals appear to hold frozen motion in their grain; walk around them and you’ll notice that certain slabs seem to twist as the light moves, their stripes accentuating edges and hollows. This is stone that remembers pressure and heat, tectonic collisions and continental drifts. To build with it was to borrow the island’s deepest age and stand it up in human time.

The setting is no accident either. The ridge on which Calanais stands is a small eminence with long views to the hills of Great Bernera and, in clear weather, out across the sea lochs to the west. The site is visible from the water, and from neighboring slopes, so the stones perform both locally and at distance—beacons of presence. In good light, the ridge becomes a stage; in weather, the stones are almost theatrical—black against cloud, silver against sun, their edges catching rain. Even before you consider alignments and avenues, the landform itself is part of the monument’s design.

The Shape of a Ceremony

Seen from above, Calanais looks like a cross: a central ring with stone rows extending to the east, south and west, and a long, double row forming an avenue to the north. At the center stands a tall monolith, nearly five meters high, around which thirteen stones compose the ring. Inside the circle lie the remains of a chambered cairn, a later addition whose low footprint nestles against the great central slab. The avenue to the north runs for the better part of a football field, narrowing toward the circle so that the perspective draws you forward. If you enter this way, the site reveals itself as an experience: the slow approach along the rows, the moment of crossing into the ring, the forced awareness of both enclosure and horizon.

It’s easy to over-interpret the cross form as symbolic of something that would not exist for thousands of years; the resemblance is coincidental, a trick of the plan. What matters more is how the arrangement organizes bodies and sightlines. The avenue frames the approach; the ring creates a threshold and center; the radial rows point outward, reminding you that this is not a cloister but a node in a landscape. People, sky, stone and ground are arranged to meet.

How Old—and How We Know

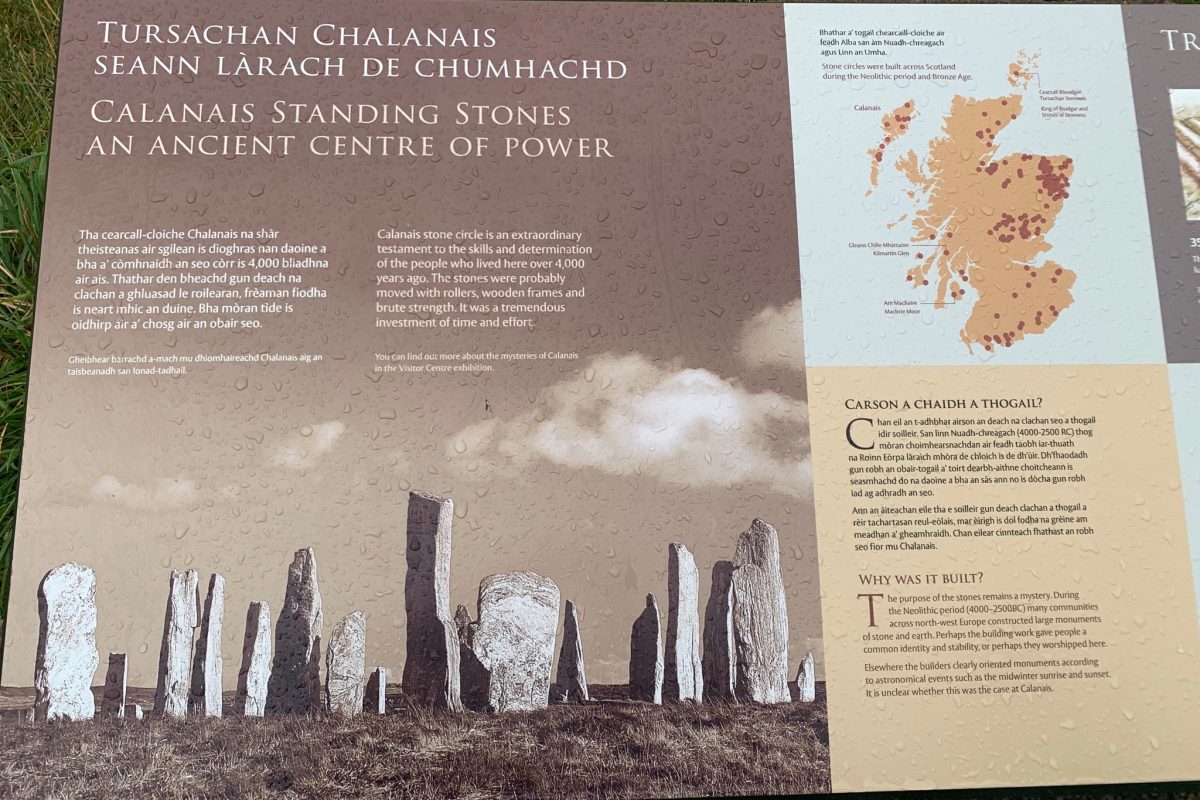

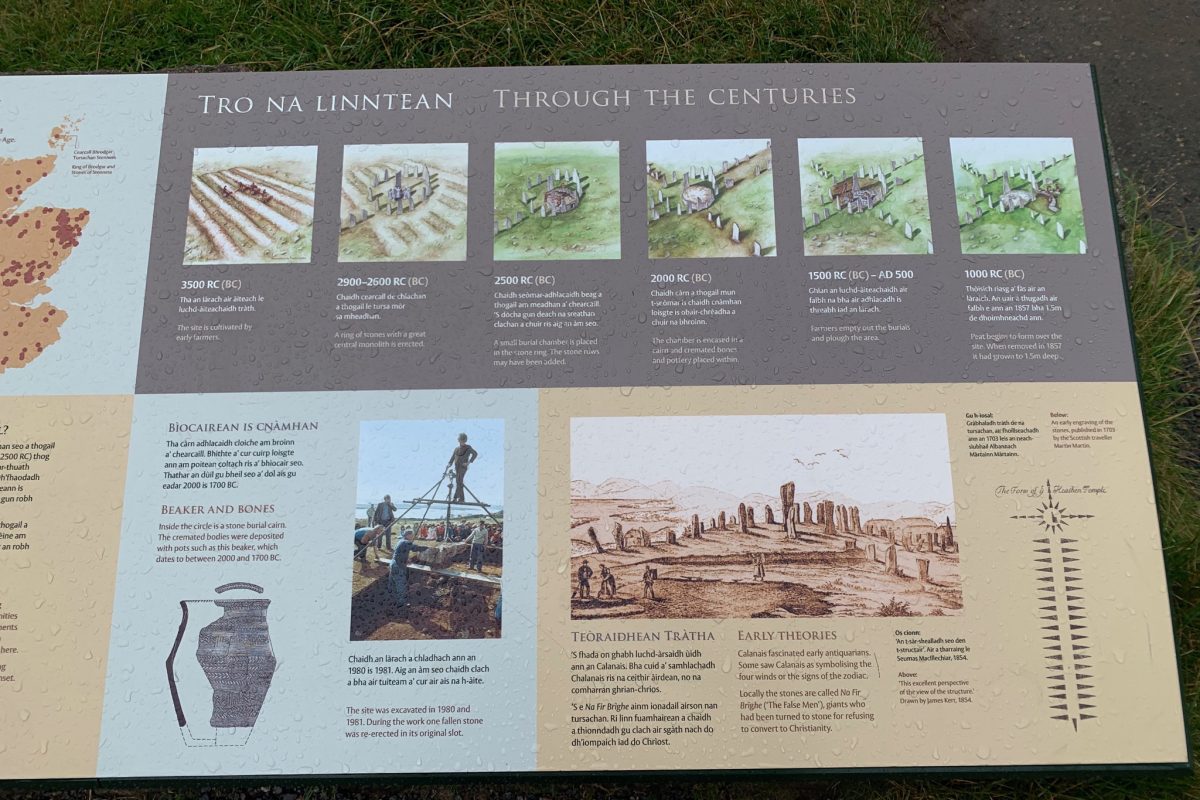

The story of when Calanais was built comes from archaeology and the patient work of excavation. The main circle belongs to the late Neolithic, typically dated around the third millennium BC. The cairn inside the ring was inserted later, during the early Bronze Age, making clear that this wasn’t a single-event construction but a place that changed as communities changed. Evidence suggests that ritual use—whatever that meant here—continued for many centuries before the site was gradually abandoned.

Why abandonment? Climate seems to be part of the answer. From about the second millennium BC onward, changing weather encouraged the development of peat, a slow blanket that can both obscure and preserve. Over generations, peat accumulated around the stones, shortening them visually and subduing the surrounding ground. By the time people “rediscovered” the circle in the nineteenth century, they had to cut away meters of peat to reveal the monument’s original drama—its full height, the cairn inside, the steps into the ring.

The Labor of Making

It’s tempting to imagine Calanais appearing in one burst of Megalithic inspiration, but raising a monument like this took sustained community labor. Quarries for the gneiss would have been local but not necessarily adjacent; stones this size demand careful selection and preparation. Think of the teams, the ropes, the rollers, the timber levers, the slow transport across wet ground, the levering and packing to set each monolith upright—a choreography of construction as intricate as the rituals that might have followed.

This was not simply spectacle-building. Communities in the Hebrides at this time were farming, managing livestock, shaping wood and bone and stone, weaving social relationships across sea and land. Dedicating time and effort to Calanais meant diverting labor from other tasks. The monument’s scale and persistence across generations suggest that the people who built and maintained it found real value—perhaps power, identity, or connection—in gathering here and keeping the place alive.

Moonlight on the Ridge

If there is a single phenomenon that has captured modern imaginations at Calanais, it is the major lunar standstill, a cycle of about 18.6 years when the Moon rises and sets at its most extreme points on the horizon. On certain standstill nights, the full Moon skims low along the southern skyline, close to the outline of the hill range locals call the Sleeping Beauty—the supine form of a woman lying on her back. From particular vantage points near the stones, the Moon seems to roll along the ridgeline before dipping and sending a low light through the avenue toward the circle.

Was Calanais designed for this? Some scholars say yes, emphasizing how the avenue channels attention north-to-south and how local horizon features “catch” the Moon. Others counsel caution: the complex was built and modified over centuries, and alignments can arise accidentally in a setting rich with ridges. Yet even the skeptics agree that the experience of the standstill here is powerful enough to have mattered to people who watched the sky. At minimum, Calanais afforded a stage on which predictable celestial events could be anticipated, narrated and ritualized—turning astronomical knowledge into social authority.

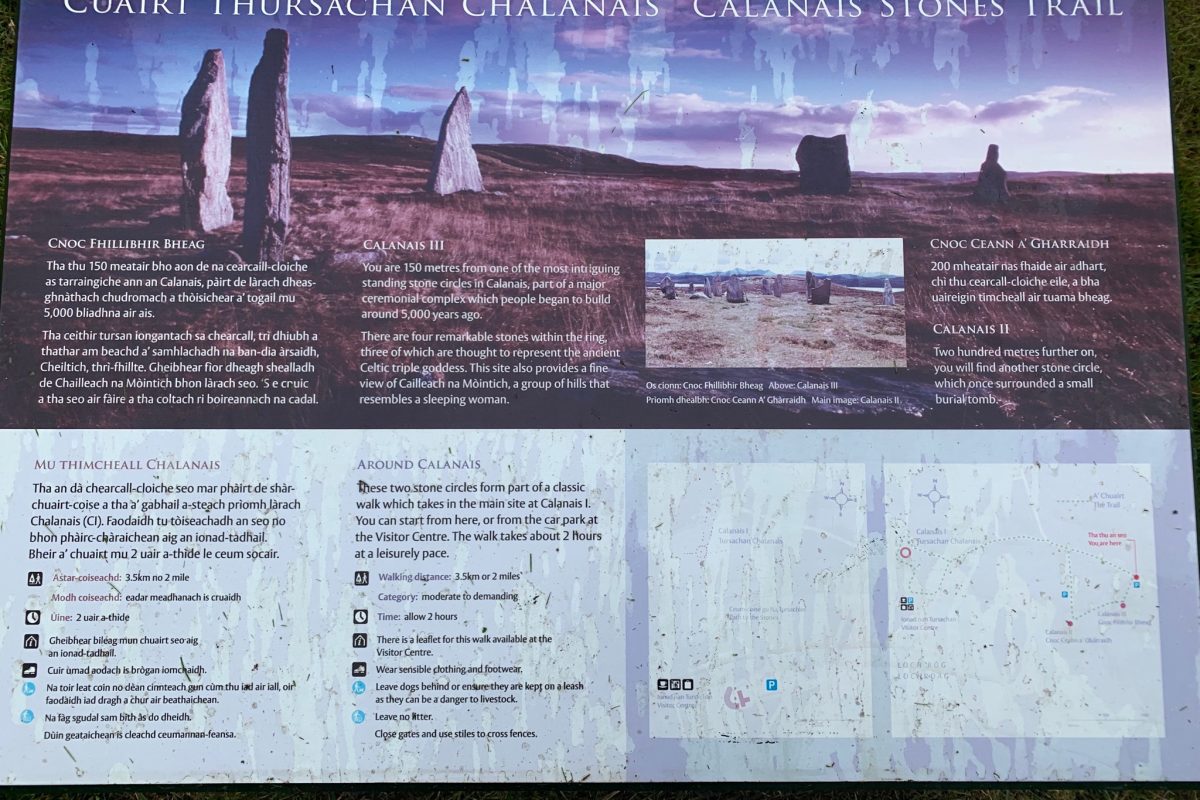

The Wider Web: Calanais II, III, and Beyond

One of the profound realities of Lewis is that Calanais is not a singleton but the hub of an entire ritual landscape. Within a few kilometers lie at least a dozen other monuments: circles, arcs, alignments, single stones. Two near neighbors—often called Calanais II (Cnoc Ceann a’ Gharraidh) and Calanais III (Cnoc Fillibhir Bheag)—stand just over a kilometer away. Calanais II sits on another ridge, its oval of stones encircling a small, later cairn; traces found there suggest that timber may have preceded stone, hinting at an earlier phase of monument-making now mostly gone to peat and time. Calanais III preserves concentric elliptical rings, its inner stones taller than the outer—a design that feels intimate and complex compared to the axial drama of the main site.

Elsewhere on the moors, smaller rings and isolated uprights catch your eye from the single-track roads or from the slopes above sea lochs. Together, these monuments imply centuries of continuous attention to this landscape—not a one-off construction but a tradition in which communities returned to, reconceived, and re‑inscribed sacred space. Visit several sites in a day and you begin to read the hills differently. You notice knolls that command views. You feel how water and land interlock. You start to see how a person five thousand years ago might have arranged stones to converse with distance.

Myths, Names and the Shining One

No monument lives five thousand years without collecting stories. In Gaelic, the stones have been called Fir Bhreige—“the false men”—which echoes a common European motif about people turned to stone for violating sacred duties. In later traditions, a figure known as the Shining One is said to walk the avenue at midsummer sunrise, his coming announced by the call of a cuckoo. Scholars can argue about the antiquity of these tales, but they are revealing even as later inventions: they make the avenue a path of arrival, the circle a place where something—or someone—enters the human world at a moment marked by sky.

Names matter, too. The local preference for Calanais (Gaelic) over Callanish (Anglicized) is more than orthography; it’s a reminder that for all the global fascination, this is a community landscape with a living language and present-day meanings. Tales told around kitchen tables, in schoolrooms, and on windy verges by local guides are part of how the site continues to work—binding visitors to place through story as surely as through stone.

From Quiet to Canon

For centuries, the stones slept under peat. When nineteenth-century peat‑cutters and landowners cleared the site, revealing the full height of the monoliths and the cairn within, Calanais quickly entered the imagination of scholars and travelers alike. Early antiquaries marveled and speculated; later, surveyors mapped and measured; archaeologists excavated; photographers and painters translated the stones into light and pigment. In the twentieth century, Calanais became a touchstone for archaeoastronomy, a place where hypotheses about prehistoric sky knowledge could be tested against horizon, row and ring.

Along the way, the circle entered popular culture and modern story as well. You can find the silhouette of Calanais on book covers, in films, in tourism posters, even echoed in fictional stone circles on screen. None of that is a replacement for the place itself, but it demonstrates how the monument has shifted from local landmark to global icon while remaining rooted in the same ridge above the same loch, under the same temperamental sky.

How to Experience the Stones

Guidebooks will give you directions and maps; what they can’t provide is the way to feel the site. That arrives only if you allow yourself time. If you can, visit twice: once in the soft bookends of the day—dawn or dusk—when wind speaks through the stones and the light wraps edges in gold or blue; and once at high noon, when the monument stands in hard clarity and the avenue’s geometry is sharp. Walk the north avenue slowly, letting the double lines narrow your attention. Stand at the central monolith and look outward, following the east, south and west rows with your eyes. Walk the circumference of the ring counterclockwise and then clockwise, noting how the stones’ faces differ—some smooth, some rough, some with surprising curves.

Then step outside the ring and look in. The monument is about relationships—inside to outside, far to near, low to high, human scale to sky scale. Listen for the immediate sounds (wind, birds, distant water) and watch the subtle ones (shadows crawling across gneiss, light that makes stripes appear and then vanish). The stones do not reward hurry. If you share the site with others, it helps to remember that silence is a kind of offering here.

Ethics and Care

Calanais endures because people have cared for it—first by building and ritualizing it, later by protecting it as an archaeological site. That care is now part of the visitor’s task. Stay on obvious paths where you can, avoid climbing on stones or cairn remains, and resist the urge to leave marks. If you carry a drone, ask yourself whether the shot is worth the disturbance to birds or to those who came for quiet. And perhaps most importantly, recognize that you are standing in a living cultural landscape, not a backdrop. There are crofts and homes nearby; there is a Gaelic-speaking community to whom this place is more than an Instagram radius.

Reading Meaning Without Reducing Mystery

Every generation frames Calanais in the questions it knows how to ask. In the nineteenth century, the stones were “druidic” because that was the vocabulary at hand; in the twentieth, they were “observatories” because science offered a new lens; in the twenty-first, they become nodes in discussions of land, memory, and identity because we are asking how places make and remake communities. The truth is that Calanais likely held many meanings at once. It could shape seasonal gatherings, mark celestial rhythms, anchor funerary rites, bind alliances, and help people imagine themselves in relation to the land and the heavens.

Insisting on a single function risks flattening a monument that has already shown itself capable of evolving. The cairn inserted into the ring, the avenue that reorients the approach, the satellites that amplify the core—all of these suggest additions and reinterpretations. If the builders could revise the place across centuries, we can accept that understanding it may remain a moving target: part archaeology, part sky-watching, part story.

A Short Walk Through Deep Time

Consider one loop you might take when the day is long and the wind cooperative. Start at the north end of the avenue. From here, the stones rise ahead as if fixed in the act of listening. Walk toward them and notice how the double row pinches your field of view until, suddenly, you’re at the threshold and the circle opens around you like a held breath released. Step into the ring and let your eyes fall to the low cairn inside—a reminder that this space once received the dead and the memory of the dead. Place your back lightly against the central monolith. You may feel the wind differently here, as if the stone makes a small pocket of stillness.

Exit to the west and follow that row outward until the circle is at your back and the avenue hinges into the landscape. Turn and take in the entire plan—the cross form legible against heather and grass. Then make your way to one of the satellites—Calanais II or III, depending on your time and knees. Approach the smaller ring and feel how your body recalibrates to a more intimate scale. Sit on a rock and watch how cloud‑shadow runs across the loch and the ridge. In that moment you are doing something very old: using stone and horizon to think with.

Why It Still Matters

Calanais could have been one more ruined thing in a wet field. Instead, it has become a shared image of the Neolithic imagination—not because it has yielded all its secrets, but precisely because it hasn’t. The stones invite us to meet the past in a mode other than ownership or explanation. They ask us to accompany: to walk alongside, to witness, to let a place do its work without demanding that it submit to our categories. That feels, in its quiet way, radical.

There’s also a specific gift that Calanais gives to the present, which is the reminder that communities can create common ground—literal and figurative—by joining craft, knowledge and belief. It took engineering to raise these stones, yes, but also patience, ceremony, story. The result is not just a structure but a practice: a way of moving together, timing life to cycles larger than ourselves, and marking loss and renewal with forms anyone can see and feel.

The Last Light

If you are lucky enough to be there at sunset, you’ll see the gneiss blaze into color that is not quite color—something between silver and rose. The stones throw long shadows that knit the ring into one shape, then stretch the avenue farther than it looks by day. Birds lift and settle. The loch takes the sky’s attention and returns it as ripples of light. You will think, perhaps, that you have learned something important about the people who raised these stones, and then you will think that what you have learned is mostly about yourself—about what you bring to places that are older than any name you have for them.

When the light finally goes, the stones do not vanish. They stand exactly where they were, doing the work they have always done: holding space for the meeting of sky and land, the living and the dead, knowledge and story, past and present. And when you walk away down the ridge, you carry a little of that meeting with you—an inner arrangement of silence and attention, like a circle of thirteen stones around a taller memory, and an avenue leading you forward into the night.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.