I stepped onto the Royal Mile with the kind of reverence you reserve for places that have carried centuries on their back. The cobblestones beneath my boots were slick from a morning drizzle, and the air smelled faintly of malt and rain—a scent that seemed to belong to Edinburgh as much as the Castle looming behind me. Ahead, the Mile stretched like a spine, straight and proud, running from the fortress on its volcanic perch down to the quiet dignity of Holyrood Palace.

But it wasn’t the grand sweep of the street that drew me here. It was what lay hidden in its ribs: the closes.

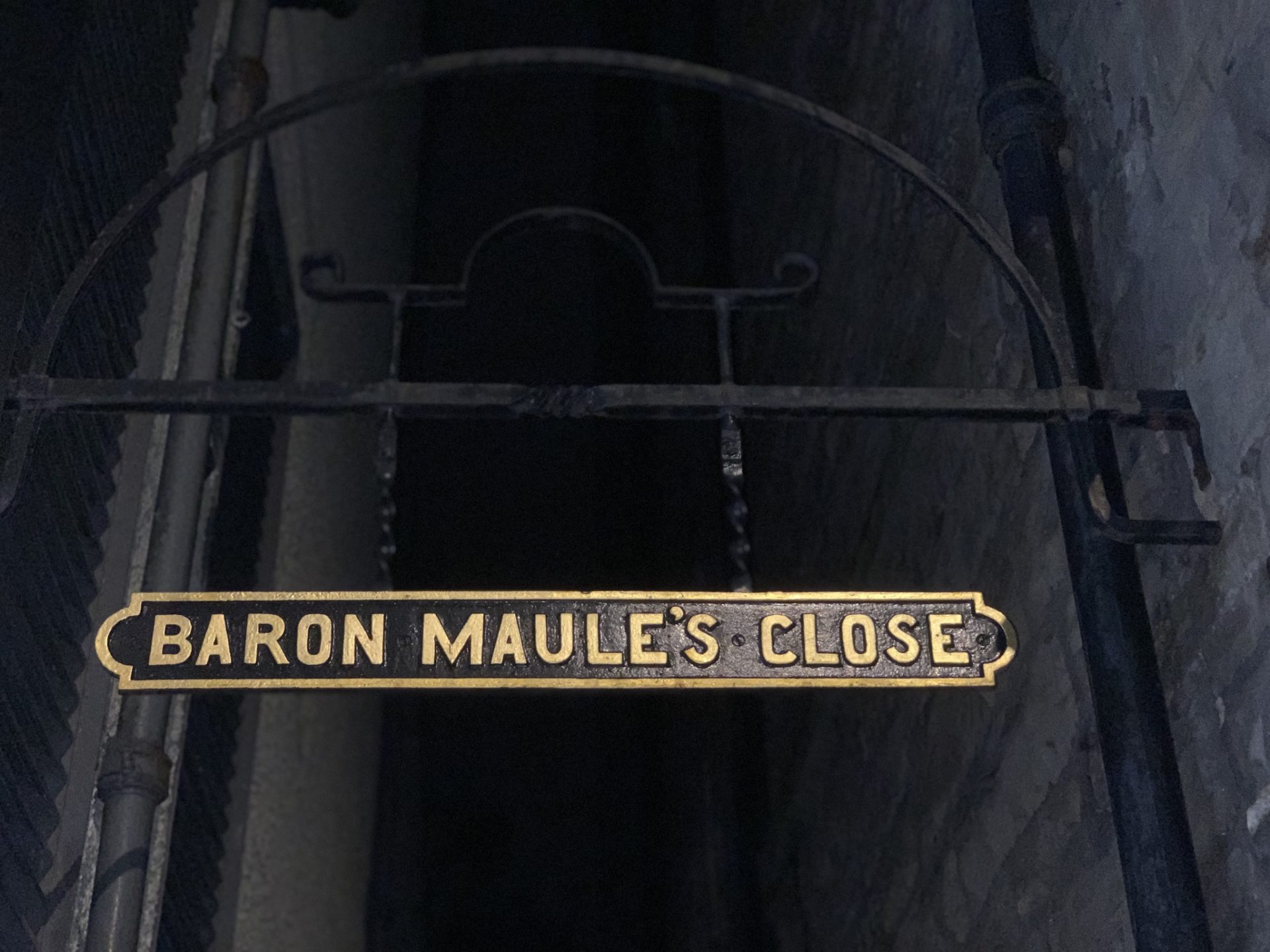

They don’t announce themselves. You have to look for them—narrow mouths between tall, soot-darkened tenements, some marked by weathered signs, others so modest you’d miss them if you blinked. Over two hundred and fifty of them, they say, threading off the Royal Mile like veins from an artery. Each one a story. Each one a secret.

I paused at the first, Advocate’s Close, and peered down its steep descent. The stone steps fell away sharply, framing a view of the Scott Monument in the distance, its Gothic spire clawing at the sky. The close was quiet now, but I imagined the clatter of boots and the murmur of voices that once filled this narrow canyon. These closes were lifelines in the Old Town, where space was scarce and life stacked itself upward. Families, merchants, lawyers, and thieves—all crammed into towering tenements, their doors opening onto these shadowed passages. They were shortcuts, marketplaces, neighborhoods, and sometimes hiding places. Today, they feel like portals.

I ran my fingers along the wall as I descended a few steps, the stone cold and damp, worn smooth by centuries of touch. The Royal Mile above was bustling with tourists and buses, but here, just a few feet in, the noise softened, replaced by the hush of stone and the faint echo of my own breath. That’s the magic of Edinburgh’s closes: they pull you out of time.

Walking the Mile

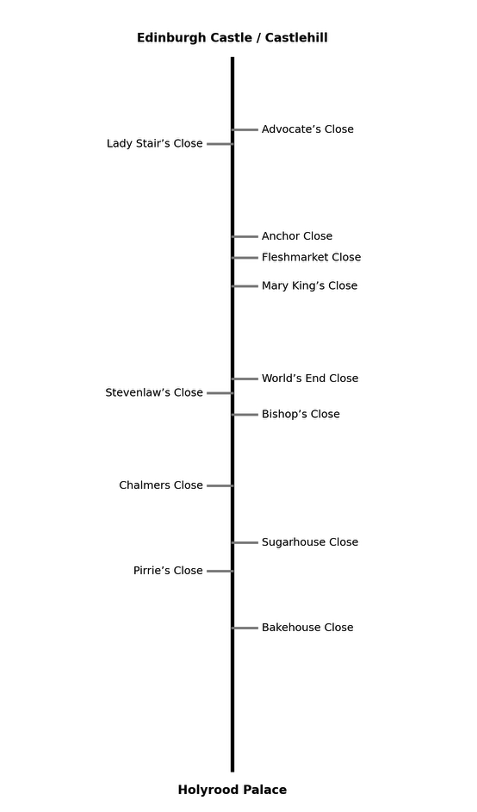

The Royal Mile is not a mile at all, though it feels like one when you walk it slowly, letting the weight of history press against your shoulders. It’s a mile in spirit—a stretch of stone that binds Edinburgh Castle to Holyrood Palace like a thread through a tapestry. And along that thread, the closes hang like beads, each one a doorway into another world.

I started down from Castlehill, where the Mile begins in a flourish of battlements and bagpipes. The sound of the pipes drifted like smoke, curling through the damp air, and I smiled at the thought that this music had been echoing here for centuries. The street was alive with tourists clutching cameras and locals weaving through the crowd with the practiced grace of people who know every uneven stone. But my eyes weren’t on the bustle—they were on the gaps.

The first thing you notice, once you start looking, is how the closes interrupt the rhythm of the buildings. Tall tenements rise like cliffs, their windows stacked in improbable tiers, and then—suddenly—a slit of shadow opens between them. Some are marked by carved lintels, others by modest signs, their letters faded by rain and time: Advocate’s Close, Writer’s Close, Anchor Close. Names that sound like chapters in a book you want to read.

I walked slowly, letting my gaze slip into each opening. Some closes plunge downward in steep flights of stone steps, their walls pressing close like conspirators. Others run level, straight as arrows, ending in a patch of sky or a courtyard where ivy clings to the stone. A few are barred by gates, their secrets locked away, while others beckon with the promise of discovery.

The Royal Mile itself is a stage—grand, noisy, full of spectacle. But the closes are the wings, where the real drama happened. In the 16th and 17th centuries, these narrow passages were arteries of life. Edinburgh was a city hemmed in by walls, so it grew upward instead of outward. Tenements soared ten, twelve stories high, their timber frames groaning under the weight of humanity. The closes were the threads that stitched this vertical world together, leading from the main street to hidden courts and gardens, to breweries and bakehouses, to homes where generations lived and died in rooms barely big enough for a bed.

I stopped at Lady Stair’s Close, drawn by the promise of quiet. It opened like a sigh between two buildings, leading to a courtyard where the Writers’ Museum now stands. The stones here seemed to hum with words—Burns, Scott, Stevenson—all ghosts of the pen who once walked these streets. I stood for a moment, imagining Scott striding past, his mind full of battles and ballads, and felt the peculiar intimacy of this city. Edinburgh doesn’t just display its history; it whispers it in your ear.

Back on the Mile, I noticed how the closes shape the rhythm of the walk. You can’t help but glance sideways, wondering what lies beyond each shadowed mouth. Some names tell their own stories: Fleshmarket Close, where butchers once hawked their wares; Fishmarket Close, fragrant with the memory of scales and salt; Old Stamp Office Close, echoing with the clink of coins and the scratch of quills. Others are more enigmatic—Bishop’s Close, Chalmers Close, Stevenlaw’s Close—names that hint at power, trade, and family pride.

As I moved toward the Lawnmarket, the Mile narrowed, the crowd thickened, and the closes seemed to multiply. They were everywhere now, like secret invitations. I ducked into one at random—Stevenlaw’s Close—and found myself in a canyon of stone, the walls rising sheer on either side. The air was cooler here, tinged with the earthy scent of moss. My footsteps echoed, and for a moment, I felt utterly alone, as if the city had folded me into its private heart.

That’s the thing about Edinburgh’s closes: they’re not just shortcuts. They’re experiences. Each one is a shift in atmosphere, a change in light, a sudden plunge into history. You step off the Royal Mile and the world tilts. The chatter fades, the sky narrows, and you’re walking through centuries.

I emerged back onto the Mile, blinking at the brightness, and continued downward toward the High Street. The closes here were busier, some lined with shops and cafés, their old stones repurposed for modern appetites. But even amid the hum of commerce, the past clung like mist. I passed Fleshmarket Close and thought of carcasses swinging from hooks, blood pooling on cobbles. I passed Anchor Close and pictured printers hunched over presses, ink staining their fingers as they churned out pamphlets that would stir revolutions.

Every close is a story, and the Royal Mile is a library. You just have to know how to read its spines.

Famous Closes of the Royal Mile

The Royal Mile is a river of stone, but its tributaries are what make it fascinating. Each close is a doorway into another Edinburgh—a city within the city, layered with centuries of life. Today, I wanted to linger in the most storied of them, the ones whose names echo through guidebooks and whispered recommendations.

Advocate’s Close

I began where I had paused earlier, at Advocate’s Close. It’s one of the most photographed, and for good reason. The descent is steep, the steps worn smooth by generations of boots, and at the bottom, the view opens like a secret: the Scott Monument rising in the distance, its Gothic spire clawing at the sky. I stood there for a long moment, letting the perspective sink in.

The name comes from Sir James Stewart, Lord Advocate in the late 17th century, whose house once stood here. I imagined him sweeping through these stones in his robes, the weight of law on his shoulders. Today, the close hums with quieter ambitions—tourists angling for the perfect shot, locals slipping down to Cockburn Street. But the stones remember. They always do.

I traced the wall with my fingertips, feeling the chill of centuries. The Royal Mile above was a carnival of sound—bagpipes, chatter, the rumble of buses—but here, just a few steps down, the noise thinned to a whisper. That’s the magic of the closes: they fold the city inward, away from spectacle, into intimacy.

Mary King’s Close

If Advocate’s Close is a postcard, Mary King’s Close is a confession. You don’t stumble into this one; you descend deliberately, guided by history and a ticket stub. Beneath the City Chambers lies a warren of rooms and passages, sealed for centuries and now opened like a time capsule.

I joined the tour, though I kept my thoughts to myself. The air was cool and faintly musty, the kind of smell that clings to old stone and older stories. Mary King was a merchant’s daughter, and in the 17th century, this close was a bustling neighborhood. Then came the plague. Families were locked in their homes, the sick marked with painted crosses, and death moved through these rooms like a shadow.

As I walked through the dim corridors, I felt the press of history—not romantic, but raw. These were not ruins; they were remnants of lives abruptly ended. The guide spoke of myths and ghosts, but I didn’t need specters to feel the weight of it. The silence was eloquent enough.

When I emerged back into daylight, the Royal Mile seemed almost indecent in its brightness. I paused, breathing in the cool air, and thought about how cities carry their tragedies like scars—hidden, but never erased.

Fleshmarket Close

Further down, near the High Street, I found Fleshmarket Close. The name alone is a story, blunt and unapologetic. In the 18th century, this was where butchers plied their trade, and I could almost smell the iron tang of blood in the air, though today it’s just stone and shadow.

The steps here are steep, plunging toward Market Street, and as I descended, the city shifted again. The Royal Mile receded, and the soundscape changed—quieter, cooler, the echo of my boots bouncing off the walls. I imagined carcasses swinging from hooks, merchants shouting prices, dogs skulking for scraps. Life was visceral here, survival unvarnished.

Now, the close leads to modernity—bars, restaurants, the hum of Waverley Station beyond. But the name clings like a ghost, reminding you that Edinburgh’s elegance was built on blood and bone.

Anchor Close

Anchor Close is easy to miss, tucked between shops near the High Street. I slipped in and felt the world contract. The passage is narrow, the walls close enough to brush with both elbows, and the light fades quickly.

This close was once the beating heart of Scottish printing. In the 18th century, William Smellie edited the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica here, ink staining his fingers as he shaped knowledge for the world. I thought about that as I walked, the irony of such vast ambition housed in such a cramped space.

At the bottom, the close spills onto Cockburn Street, a curve of Victorian charm. But for me, the real beauty was in the contrast—the grandeur of ideas born in a passage barely wide enough for two men to pass.

Bakehouse Close

If Anchor Close whispers of intellect, Bakehouse Close smells of hearth and hunger—at least in memory. In the 16th century, this was where bread was baked for the Old Town, and the name still carries that warmth.

I ducked in, and the world softened. The close opens into a courtyard, its stones mellowed by time, and for a moment, I felt as if I’d stepped into a painting. Outlander fans flock here for its cameo as Jamie Fraser’s print shop, but for me, the charm was simpler: the sense of continuity. People have been coming here for sustenance—literal or literary—for centuries.

I stood in the courtyard, listening to the hush, and thought about how cities feed us in more ways than one.

Lady Stair’s Close

Finally, I returned to Lady Stair’s Close, drawn by its quiet elegance. The courtyard cradles the Writers’ Museum, a shrine to Scotland’s literary giants, and the air feels charged with words. Burns, Scott, Stevenson—their names etched into stone, their voices lingering like perfume.

I wandered the courtyard slowly, my footsteps soft on the worn flagstones. The Royal Mile was just a few steps away, but here, time pooled like water in a hollow. I thought about how these closes are not just passages; they’re pauses. Places where the city exhales, and you can hear its heartbeat if you listen closely.

By the time I stepped back onto the Mile, the light was thinning, and the stones glowed like embers. I had walked through centuries without leaving the city center, and the thought made me smile. Edinburgh hides its riches in plain sight, but you have to be willing to slip sideways, into shadow, to find them.

Hidden and Lesser-Known Closes

By the time I reached the Canongate, the Royal Mile had loosened its grip. The crowds thinned, the air felt softer, and the closes seemed to multiply like secrets. These were not the famous ones with their glossy postcards and guided tours. These were the quiet passages, the ones that keep their stories close to the chest.

I’ve always loved the names. Edinburgh doesn’t do bland. It gives you poetry and blunt honesty in equal measure. World’s End Close—how could you not step into that? The name harks back to the days when the Netherbow Port marked the city’s boundary. For those who never ventured beyond, this was the edge of existence. I stood at its mouth, imagining the psychological weight of that gate, the sense that beyond lay wilderness and uncertainty. Today, the close leads to pubs and apartments, but the name still tastes of finality.

Further along, I found Stevenlaw’s Close, a narrow slit that feels almost defensive. It’s named for a 17th-century merchant, but the stones don’t care about commerce now. They care about silence. I walked in, the light dimming with every step, and felt the city fold around me like a cloak. The air was cool, tinged with moss, and my footsteps echoed like questions. At the far end, a patch of sky opened suddenly, startling in its brightness. That’s the rhythm of these closes—compression and release, shadow and light.

Then there’s Bishop’s Close, which sounds ecclesiastical and, in a way, still feels it. The passage is solemn, the walls high and austere, and I couldn’t help but imagine robed figures sweeping through centuries ago, their prayers mingling with the damp air. Today, it’s just stone and quiet, but the atmosphere lingers like incense.

I ducked into Chalmers Close next, drawn by its modest sign. It’s one of those passages that feels almost forgotten, its stones worn but uncelebrated. Halfway down, I paused and listened. Nothing but the faint hum of the city beyond, like a heartbeat muffled by distance. These are the moments I love—the sense that you’ve slipped sideways into a pocket of time, unnoticed by the world.

Not all closes are solemn. Some are playful, their names like riddles. Sugarhouse Close—was there really a sugar refinery here? Yes, in the 18th century, when Edinburgh’s sweet tooth was fed by Caribbean trade. I stood there thinking about the global threads woven into these narrow spaces, the way history hides in plain sight.

And then there’s Pirrie’s Close, tucked away like a secret handshake. No grand story, no famous resident—just a name and a passage. But that’s enough. In Edinburgh, even anonymity feels storied.

As I wandered, I realized something: the lesser-known closes are not just quieter—they’re more intimate. The famous ones perform for you; these simply exist. They don’t care if you notice them. They’ve been here for centuries, and they’ll be here long after the last tourist selfie fades into digital dust.

I emerged from the last close into the fading light of the Mile, my boots slick with rain and my mind humming with names. World’s End, Stevenlaw’s, Bishop’s, Chalmers, Sugarhouse, Pirrie’s—each one a syllable in the city’s long poem. And I thought: this is why I came. Not for the grandeur of the Castle or the pomp of Holyrood, but for these narrow passages where history breathes in whispers.

Closing Reflection at Holyrood

By the time I reached Holyrood Palace, the day had begun to fold itself into evening. The light was soft, the kind that makes stone glow like old embers, and the air carried that peculiar Edinburgh hush—a silence that isn’t empty but layered, like pages in a book.

I stood at the gates for a moment, looking back up the Royal Mile. It stretched behind me like a timeline, every close a notch in its spine, every shadow a chapter. I had walked through centuries without leaving the city center, and the thought made me smile.

The palace itself was serene, its gardens breathing green against the stern geometry of the Old Town. But my mind wasn’t on grandeur. It was on the narrow passages I had slipped through, the names still humming in my head: Advocate’s, Mary King’s, Fleshmarket, Anchor, Bakehouse, Lady Stair’s, World’s End, Stevenlaw’s, Bishop’s, Sugarhouse. Each one a syllable in Edinburgh’s long poem.

What struck me most was how these closes are not relics—they’re arteries. They still pulse with life, even if that life has changed. Where once there were plague victims and printers, now there are cafés and apartments. Where butchers swung carcasses, now tourists swing cameras. The city adapts, but it never erases. It layers. And in those layers, you feel the resilience of a place that has endured fire, famine, and reformations, yet still stands proud, its secrets intact.

I thought about the rhythm of the walk—the way the Royal Mile performs for you, all pomp and pageantry, while the closes whisper. They don’t demand attention; they reward curiosity. You have to lean in, slip sideways, let the city fold around you. And when you do, you find its heart—not in the grandeur of castles or palaces, but in the damp stones of passages where ordinary lives once unfolded.

As the evening deepened, I turned away from the palace and let my gaze linger on the Mile one last time. The closes were invisible from here, tucked into shadow, but I knew they were there, waiting. Silent, patient, eternal.

And I thought: this is Edinburgh’s gift. It doesn’t just show you history—it lets you walk through it, feel it under your boots, smell it in the rain-soaked air. It hides its riches in plain sight, and if you’re willing to wander, it will give you more than views and monuments. It will give you intimacy.

I started back slowly, the cobblestones uneven beneath my feet, and felt a quiet gratitude. For the stones, for the shadows, for the names that cling like moss. For the sense that in this city, time isn’t a straight line—it’s a spiral, winding through closes that lead not just to courtyards, but to centuries.

And as the first lamps flickered to life along the Mile, I whispered a promise to myself: I’ll come back. Because Edinburgh isn’t a place you visit once. It’s a place you return to, again and again, slipping into its closes like secrets shared between old friends.