The long road to April 16, 1746—and the long shadow it cast over Scottish history

Standing on Culloden Moor, five miles east of Inverness, you feel the wind first. It moves across the heather and peat in a steady hush, flattening the grasses as if reenacting the final charge that ended a cause. On April 16, 1746, this bleak ground hosted the Battle of Culloden, the last pitched battle fought on British soil and the violent climax of the ’45 Jacobite Rising. In less than an hour, a political dream collapsed, a cultural order buckled, and Scotland’s future tilted decisively toward a new, often painful, modernity.

This is the story of how Scotland arrived at that day, what happened on the moor, and why its consequences still echo through language, law, identity, and memory.

From dynasty to dissent: the long prelude (1603–1745)

The roots of Culloden stretch back well before the first musket cracked that morning. A few milestones help set the stage:

- 1603—Union of the Crowns: James VI of Scotland becomes James I of England, uniting the crowns but not the parliaments. The Stuart dynasty straddles two kingdoms with differing religions, legal systems, and political cultures.

- 1688–89—The “Glorious Revolution”: James VII/II, a Catholic, is deposed. William and Mary (Protestant) take the throne. For many in the Highlands—especially staunchly loyal clans and Catholics—this is unlawful usurpation. The Jacobite (from Jacobus, Latin for James) cause is born: restore the Stuart line.

- 1715 & 1719—Failed Jacobite risings: The 1715 uprising under the Earl of Mar and a smaller 1719 attempt falter. In the aftermath, London invests in military roads (Wade and later Caulfeild), garrisons, and forts to penetrate Highland glens and deter rebellion. The state is learning the terrain—and how to police it.

Across these decades, the Highlands and Lowlands diverge. Gaelic-speaking, clan-structured Highlands retain kin obligations and semi-autonomous justice; the Lowlands integrate more rapidly into British—and global—markets. The tension between these worlds becomes one of Culloden’s central fault lines.

The spark of 1745: a prince, a promise, and a gamble

Into this combustible landscape steps Charles Edward Stuart—Bonnie Prince Charlie. Convinced that French aid and Highland enthusiasm will deliver the throne to his father, he sails to the Hebrides and lands on Eriskay in July 1745 with little more than audacity and a handful of companions. Many clan chiefs are wary—memories of 1715 linger—but the combination of charisma, honor, and hope proves persuasive.

Key moments on the road to battle:

- The raising of the standard (Glenfinnan, August 19, 1745).

Pipes skirl. The Stuart banner snaps in the wind. The Camerons, MacDonalds, and other clans rally. A Jacobite army is born. - Edinburgh falls, Prestonpans triumph (September 1745).

The Jacobites take Edinburgh (except the Castle). On September 21, they rout Sir John Cope at Prestonpans. The famed Highland charge—fast, terrifying, relentless—sweeps government ranks aside. The myth of invincibility blossoms. - The March into England (November–December 1745).

Buoyed by success, the army crosses the border, reaching as far south as Derby. But promised mass English and French support fails to materialize. Supply lines stretch thin. A council of war at Derby turns on a knife-edge between audacity and prudence—and chooses retreat. - The long retreat and Falkirk Muir (December 1745–January 1746).

Fighting rear-guard actions (notably Clifton Moor) the Jacobites fall back into Scotland. On January 17, they win a muddled victory at Falkirk Muir near Stirling, but command fissures and logistics woes deepen. It is a win that solves nothing. - Two armies reset (February–March 1746).

The Jacobites drift north toward Inverness, a region aligned to their principal Scottish champion, Duncan Forbes of Culloden—ironically a Hanoverian loyalist who had tried to prevent the rising. Meanwhile, Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, consolidates a disciplined, well-provisioned government army on the northeast coast, wintering and drilling around Aberdeen. - Supply crisis and strategic missteps (March–April 1746).

The Jacobite siege of Fort William fails. Food is scarce; pay is in arrears. Rivalry among commanders—O’Sullivan, Lord George Murray, and the Prince—undermines cohesion. Cumberland advances methodically along the Moray Firth, his columns shielded by cavalry and artillery. - The night before (April 15, 1746).

On Cumberland’s birthday, his men receive extra rations; the Jacobites, by contrast, are hungry and exhausted. A daring night march to surprise the government camp near Nairn is launched late. Confusion in the dark, poor roads, and sheer fatigue force an abort. At dawn, the Jacobite troops straggle back toward Culloden Moor, spent and underfed—on the very morning they must fight.

These turning points—Derby’s retreat, the failure of external support, the winter reset, and the botched night march—place a tired army on bad ground facing a larger, rested, better-armed foe. The die is cast.

Culloden, April 16, 1746: a battle in three movements

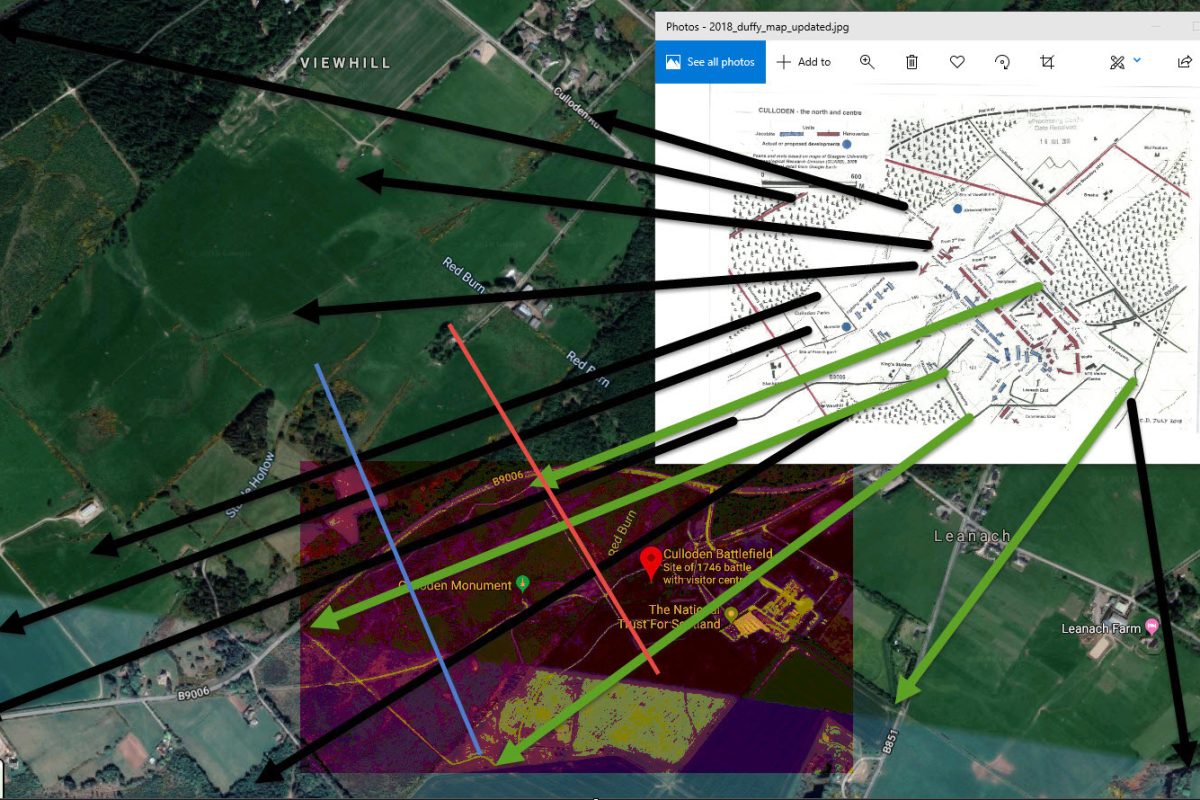

The ground and the guns.

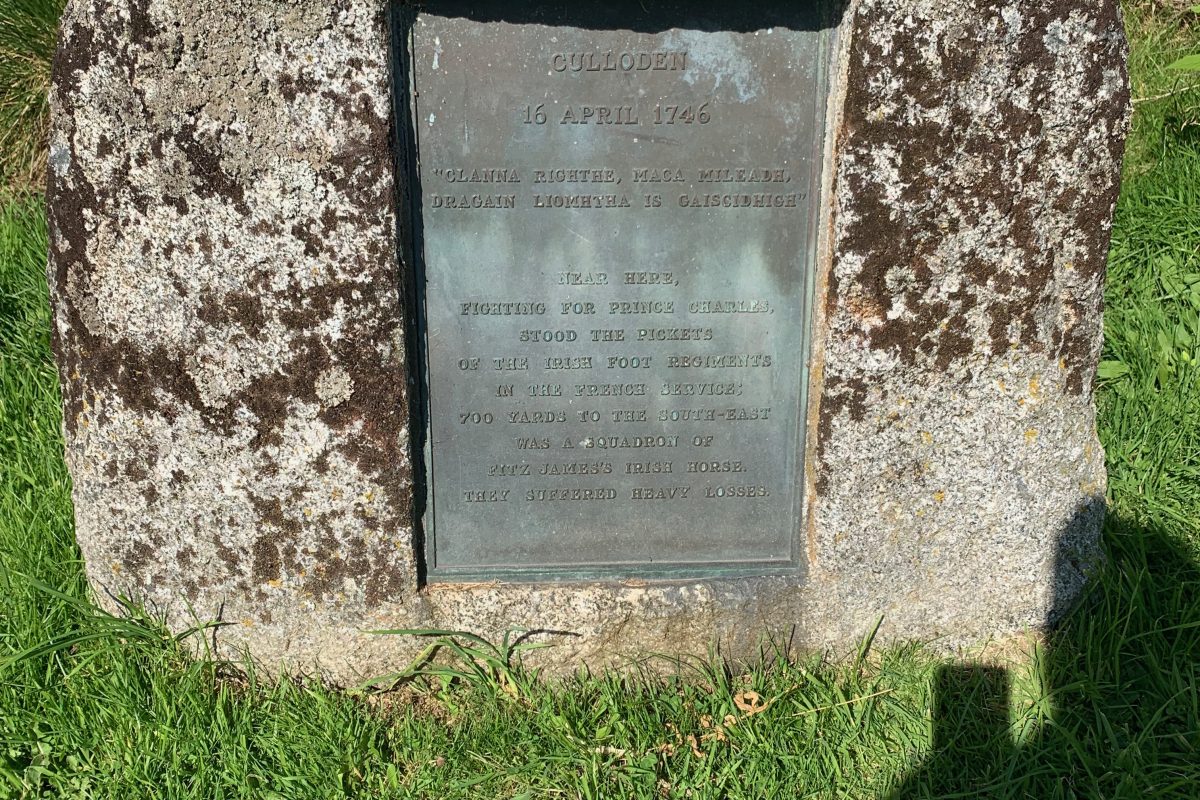

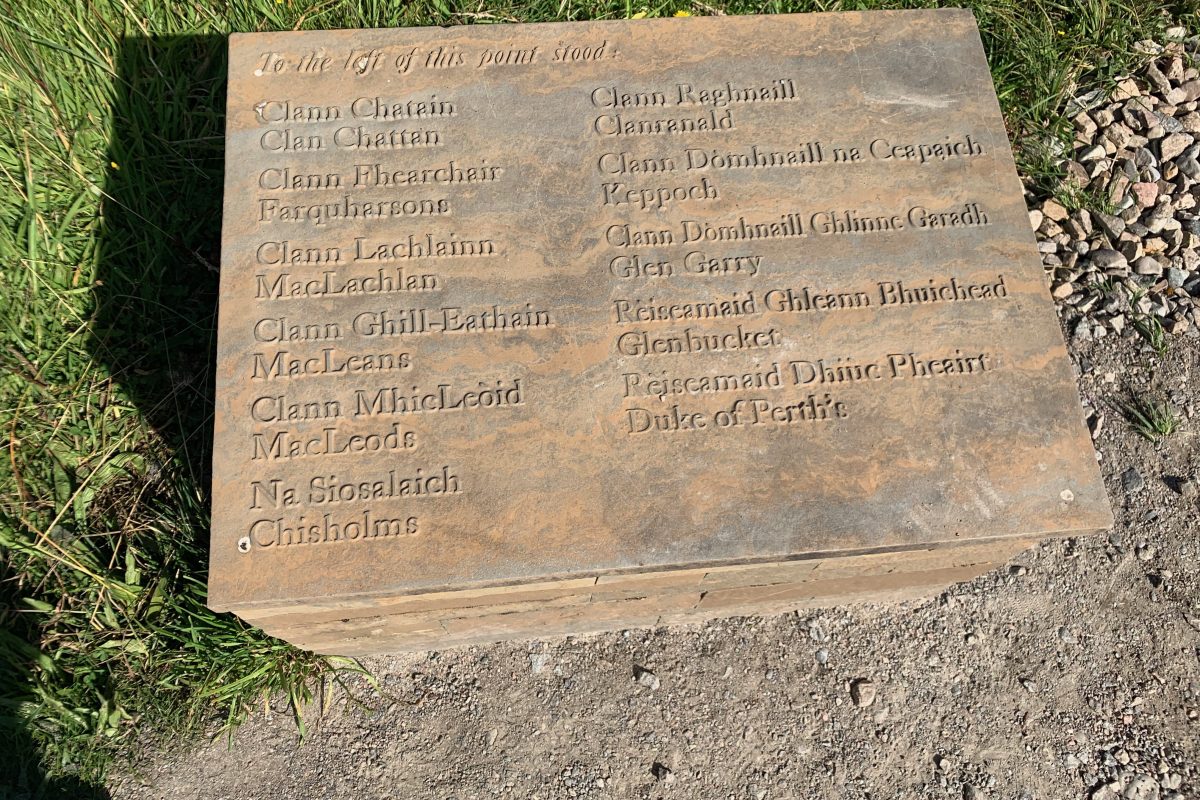

Culloden Moor is flat, open, and sodden. The Jacobite army excels on broken, close ground where a rapid charge can close before volleys bite; here, mud slows legs and wheels alike. Cumberland arrays close to the Culwhiniac enclosures and farm walls; cannon are massed along his front. The Jacobite deployment puts the traditionally proud MacDonalds on the left, a perceived slight that sours morale. The Camerons, Stewarts of Appin, the Atholl Brigade, and others hold the right. French regulars—the Irish Picquets—anchor the rear guard.

Opening salvos.

Government artillery begins a ruthless prelude. Round shot plows lanes; canister scythes tight ranks. Jacobite cannon are fewer, poorly served, and hampered by wet ground. Minutes stretch—an eternity under iron rain.

The charge—and the shattering.

At last, the Jacobite right surges forward. Mud clutches boots, and the well-drilled government line fires by platoon, staggered volleys keeping up a near-continuous blaze. Still the Highlanders come—shields up, broadswords high—and crash into the left-center of Cumberland’s line. For a heartbeat there is brutal, intimate combat. But gaps open; enfilading fire cuts into the attackers; cavalry threatens the flanks. On the left, many MacDonalds never close—the distance too great, the fire too deadly, the grievance too fresh. When the government second line steps forward, the momentum breaks. The rout begins.

Forty minutes that lasted three centuries.

Some Jacobites rally around the Irish Picquets and rear-guard cavalry to cover the retreat; many are cut down in the boggy ground toward the River Nairn. Government dragoons pursue with ferocity. By noon, it is over.

Casualties and contrast.

Roughly 1,500 Jacobites are killed or wounded; the government loses fewer than 300. Numbers vary by account, but the ratio tells the tale: uneven artillery, discipline, terrain, and logistics outweighed courage. That imbalance would shape what followed.

After the guns fell silent: punishment, policy, and the unmaking of a world

Culloden’s brutal clarity unleashed an equally brutal pacification. Cumberland’s troops swept the battlefield and surrounding glens, killing wounded, burning bothies, and seizing cattle. In London and Edinburgh, Parliament set about erasing the clan system as a political force.

Key measures and their meanings:

- Disarming and Dress Acts (1746): The Act of Proscription outlawed the wearing of Highland dress (save for those in government service) and tightened earlier disarming statutes. These laws were less about fashion than about extinguishing a visible identity linked to rebellion.

- Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act (1746): Clan chiefs’ traditional judicial powers—granting justice, raising men, exacting fines—were abolished. Authority shifted decisively to the Crown and its courts. Chiefs moved, in effect, from warlords to landlords.

- Forts, roads, and Fort George: Existing barracks (like Fort Augustus) were reinforced; an immense new fortress, Fort George at Ardersier near Inverness, would anchor Hanoverian power in the north for generations. New roads spliced glens to garrisons.

- Language and learning: The Gaelic language—heart-speech of the Highlands—encountered rising stigma. Some educational societies discouraged its use in schools; the language retreated under the twin pressures of policy and economics.

None of these statutes singlehandedly “ended Highland culture,” but together they accelerated transformations already underway. The clan system—political, legal, and economic—lost its structural bones.

From tacksmen to sheep: economic aftershocks and the Clearances

With chiefs now functioning primarily as landlords, estate management shifted toward profitability. Tacksmen (intermediate leaseholders) who had once raised men for chiefs found their roles redundant; many emigrated. As wool prices rose in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, landowners consolidated holdings, introducing large-scale sheep farms and pushing communities to the coasts or overseas. This process—varied in pace and severity across districts—is remembered as the Highland Clearances.

Culloden was not the sole cause of the Clearances, but it was a crucial hinge. By destroying the military and judicial independence of the clans, it enabled a landlord/market logic to dominate the glens—often to devastating effect. Families left for Nova Scotia, Ontario, and the Carolinas, or crowded into crofting townships along rough shores. A people who once measured wealth in cattle and kin learned to measure absence by names no longer called at ceilidhs.

Paradoxical integration: Highland regiments and a British empire

History rarely moves in a straight line. Even as Parliament restrained Highland culture at home, it recruited Highlanders for imperial wars abroad. Regiments such as the Black Watch (formalized in 1739), Fraser’s Highlanders, and Montgomery’s carried Gaelic songs and clan loyalties into the Seven Years’ War, then to North America, India, and beyond. The tartan, banned in civilian life, became a uniform of valor. Many Highland soldiers earned reputations for discipline and ferocity under the Union flag. This paradox—suppressed locally, celebrated globally—complicated Highland identity and knitted Scotland deeper into the fabric of the British state and empire.

Memory, myth, and the making of modern Scottish identity

Culloden’s meaning did not end with statutes and settlements. During the 19th century, Romanticism transformed the Jacobite story. Writers like Sir Walter Scott and composers, painters, and antiquarians reframed the Highlands as a landscape of noble melancholy, with Bonnie Prince Charlie recast as tragic hero. The royal visit of 1822 cemented a courtly embrace of tartan pageantry. Some of this revival invented traditions; some preserved fragments; all of it ensured that the Highlands would loom large in Scotland’s self-image.

The result is a layered memory:

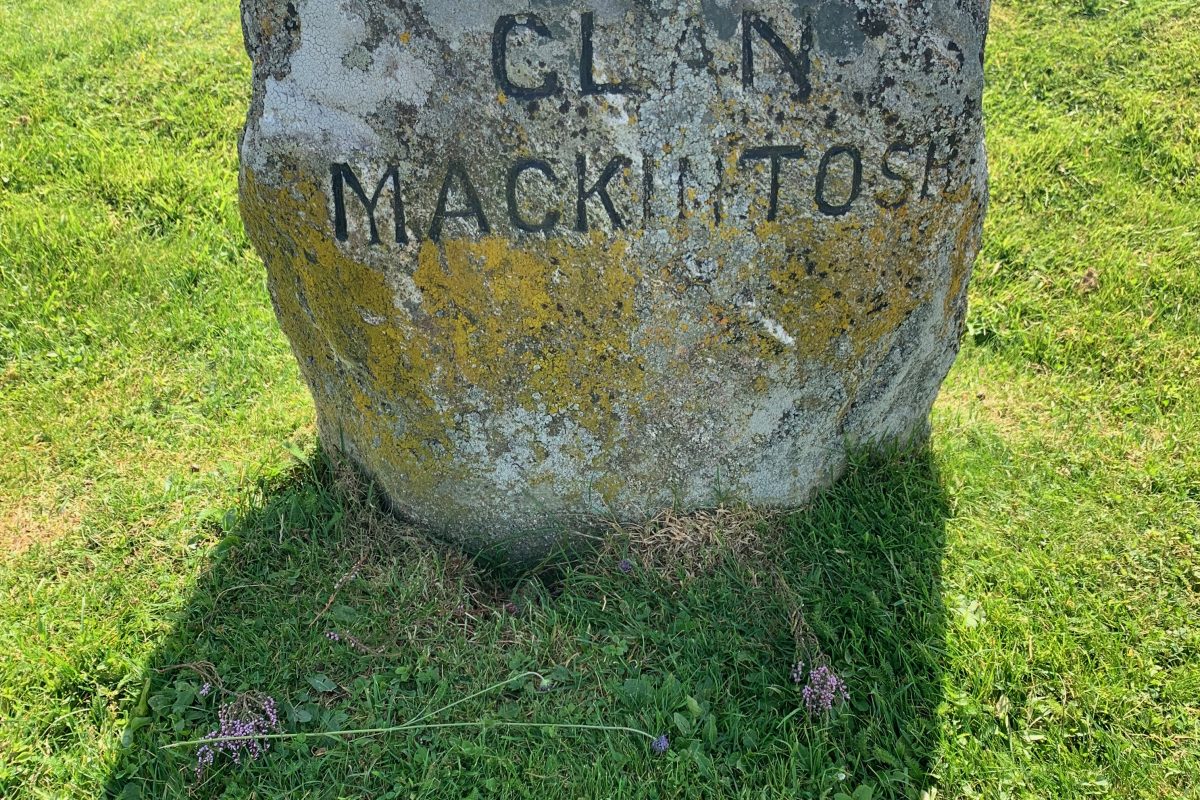

- Grief and pride: Clan memorial cairns at Culloden mark mass graves—Frasers, Camerons, Macintoshes, MacGillivrays, MacLeans—simple stones that hold centuries of sorrow. For descendants, the moor is sacred ground.

- Romance and reality: Ballads, films, and novels have sometimes gilded hard truths. The Highlands were never monochrome; loyalties in 1745 cut across geography and class. Many Highlanders fought for the government; many Lowlanders for the Prince. Culloden resists tidy myths.

- A national conversation: Today, Culloden informs debates about heritage, language revitalization, land reform, and Scotland’s constitutional future—not by dictating conclusions, but by reminding Scots that identity is contested, costly, and alive.

Walking the moor today: what to look for (and how to listen)

The Visitor Centre at Culloden uses immersive displays to step you into competing viewpoints—Jacobite and government—before you walk the field. Outside, flags mark the original lines; Leanach Cottage crouches near the center; the Memorial Cairn rises in a circle of quiet. Narrow footpaths lead to clan markers and the Well of the Dead, where oral tradition locates final acts of loyalty and loss.

A few tips for a meaningful visit:

- Give the landscape time. The moor looks plain until it doesn’t. Watch how the light changes; read the ground’s slight folds; imagine artillery sited on the firmest patches.

- Read the markers aloud. Saying the names—Fraser, Cameron, MacDonald—connects breath to stone.

- Pair sites. Nearby Clava Cairns (Bronze Age) and Fort George (post-Culloden) bracket the moor with deep past and engineered future.

- Honor the tone. Culloden is a cemetery as much as a site. Respectful silence fits the place.

Why Culloden still matters

Culloden was not simply a Jacobite defeat. It was a pivot:

- Politically, it consolidated the Hanoverian monarchy and bound Scotland more tightly to Westminster.

- Legally and socially, it dismantled the clan power structure, replacing kin-based obligation with centralized, statute-based authority.

- Economically, it cleared the path—sometimes literally—for new land uses and market disciplines that later culminated in the Clearances.

- Culturally, it accelerated the decline of Gaelic and transformed Highland identity from lived system into potent symbol—then revived that symbol in Romantic costume.

- Globally, it propelled Highland regiments into imperial service, scattering Gaelic names across the world map and entwining Scottish fortunes with British expansion.

None of these threads is simple, and not all trace back solely to the morning of April 16, 1746. But Culloden concentrated forces already in motion—state centralization, market integration, cultural change—and released them in a surge that reshaped Scotland.

Timeline: key moments that led to Culloden

- 1688–89: Deposition of James VII/II; birth of the Jacobite cause.

- 1715 & 1719: Failed risings; road and fort building begins.

- July 1745: Charles Edward Stuart lands in the Hebrides.

- August 19, 1745: Standard raised at Glenfinnan; Highland clans rally.

- September 1745: Jacobites take Edinburgh; victory at Prestonpans.

- November–December 1745: Advance into England to Derby; council decides to retreat.

- December 1745–January 1746: Skirmish at Clifton Moor; victory at Falkirk Muir; command divisions deepen.

- February–March 1746: Jacobites in Inverness area; Cumberland drills and advances from Aberdeen.

- March 1746: Failed siege of Fort William; worsening supply crisis for Jacobites.

- April 15–16, 1746: Aborted night march to Nairn; dawn exhaustion; battle on Culloden Moor; Jacobite army routed.

- Post-1746: Acts of Proscription and Heritable Jurisdictions reforms; forts, roads, and Fort George; long arc to the Highland Clearances; paradoxical rise of Highland regiments.

A final word on the wind

If you linger at dusk, the moor grows quiet enough to hear the breeze comb the heather. It sounds like surf, or distant marching, or perhaps the soft murmur of names. Culloden is not a parable with a single moral. It is a place where politics met landscape, where courage could not compensate for poor ground and empty bellies, and where a nation’s story bent in ways that were both liberating and grievous. To walk the field is to accept complexity—honor and tragedy, myth and record, loss and endurance—carried on that wind and into the present.

Planning your own exploration

- Base yourself in Inverness for easy transport, food, and lodging.

- Allocate half a day to the Visitor Centre and battlefield; add Clava Cairns and Fort George if time allows.

- Best seasons: Spring and autumn bring stark beauty without peak crowds; carry layers—the moor is exposed.

- Read before you go: Even a short primer on the ’45 will deepen every step on the ground.

Culloden is not only about the past; it is a mirror for questions that never quite leave us—about loyalty, state power, cultural survival, and what we owe one another when history turns hard.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.