A Candle in Two Kingdoms: Writing on the Anniversary of Mary, Queen of Scots

Every anniversary invites a particular kind of listening. Not the loud, modern kind—hot takes and hurried summaries—but the older kind, the way a chapel hears footsteps or the way a river remembers a bridge. When the calendar turns to the dates that bracket the life and death of Mary Stuart—Mary, Queen of Scots—history feels less like a ledger and more like a long corridor of doors. Open one and you smell candlewax, damp stone, iron, velvet. Open another and you hear Latin prayers, court music, the clatter of hooves, and a prisoner’s quiet insistence that she is still a queen.

Mary’s story has always traveled with its own weather: romance and dread; a bright courtly spring and a storm of faction; the intimacy of marriage and the hard geometry of politics. It is tempting to treat her as a symbol—a Catholic martyr, a reckless romantic, a tragic pawn, a dangerous claimant. But anniversaries do not ask us to pick a single mask. They ask us to look again at the whole face, and at the world that demanded she become both sovereign and sacrifice.

This is a life that begins with a crown placed on an infant’s head and ends with a blade that severed not only a neck, but a century of anxious hopes and fears. Between those two moments stretches a human story: a girl raised in French splendor, a young widow returned to a Scotland sharpened by reform, a queen pulled between old faith and new forces, a mother who would never raise her child, and a prisoner whose signature—written in ink—could not halt the wheels of power.

So let us step through the doors, one by one.

I. The Crown in the Cradle

Mary Stewart was born on 8 December 1542 at Linlithgow Palace, into a realm that already trembled with its own contradictions. Scotland was a kingdom of fierce regional loyalties, nobility that guarded its privileges like border fortresses, and a monarchy that relied on alliances as much as blood. Mary’s father, James V of Scotland, had spent much of his reign balancing noble factions while trying to keep Scotland’s relationship with France strong against English pressure.

Six days after Mary’s birth, James V died—exhausted, ill, and dispirited by military defeat. And so, before Mary could focus her eyes, she inherited a kingdom.

On 14 December 1542, Mary became Queen of Scots. A baby-queen is, by necessity, a mirror held up to others: regents, lords, rivals, and foreign monarchs who see in her small figure a chance to shape Scotland’s future. In Mary’s case, the struggle began almost immediately. England’s king, Henry VIII, wanted the infant queen betrothed to his son Edward. The match promised a political fusion—Scotland bound to England through marriage rather than war.

But Scotland’s nobility did not agree on Scotland’s destiny. Some leaned toward England; others clung to the “Auld Alliance” with France; many simply wanted Scotland to remain Scottish and their own power intact.

The result was not a neat diplomatic contest but violence: the campaign later called the “Rough Wooing”—England’s attempt to “court” Scotland by force. Towns were burned, fields churned into ash and mud, and the idea of Mary as a bride became a battlefield.

By the time Mary was five, Scottish leaders had decided that the safest place for their queen was not in Scotland at all.

II. A Queen Raised in Another Kingdom

If Mary’s infancy was a Scottish storm, her childhood became a French garden.

In 1548, Mary was sent to France, both as a political safeguard and as the intended bride of the French heir, Francis, Dauphin of France. In French hands, Mary would be protected from English capture and would cement Scotland’s alliance with France through marriage.

This was not exile in the bleak sense. Mary arrived into a world of elegant ritual: tapestries, masques, courtiers who could turn conversation into performance. She was educated like a Renaissance princess—languages, music, poetry, embroidery, dance, and the subtle arts of court survival. She became fluent in French, and also learned Latin, and likely a working knowledge of other tongues used among European elites. She grew tall, striking, and poised, with an instinct for ceremonial power.

In France, Mary learned how monarchy looked when it was stable: a crowned authority underwritten by wealth, institutions, and a cultivated aura of inevitability. Scotland would offer her something very different: a throne surrounded by bargaining, the constant threat of rebellion, and a religious transformation that made yesterday’s “obvious” truths suddenly contested.

But while Mary was learning courtly grace, history was rearranging the furniture of Europe.

The Protestant Reformation was remaking alliances, loyalties, and the very language of legitimacy. Kings and queens were no longer merely political; they were spiritual symbols. A monarch’s faith could be seen as a national fate. And Mary—a Catholic queen—would soon return to a Scotland increasingly shaped by Protestant conviction.

For now, though, France seemed to promise her not only safety but magnificence.

III. The Bright Marriage: Mary and Francis

On 24 April 1558, Mary married Francis, the Dauphin. She was fifteen; he was fourteen. It was a dynastic union that folded Scotland tighter into France’s orbit. It also made Mary, in the eyes of some, a threat to England: because Mary had a claim—through her Tudor grandmother Margaret—many Catholics considered her a more legitimate heir to the English throne than Elizabeth I, whose legitimacy was questioned by those who rejected Henry VIII’s break from Rome.

When Henry II of France died in 1559, Francis became King Francis II, and Mary became Queen Consort of France—a dual royal identity that looked dazzling on paper: Queen of Scots by birth, Queen of France by marriage.

But the French crown proved a brief costume. Francis was sickly, and the political arena around him was dominated by powerful families—especially the Guise, Mary’s maternal relatives, who were deeply Catholic and influential. Their prominence inflamed factional tensions in France and sharpened fears in Protestant circles about Catholic dominance.

Then, in December 1560, Francis II died after barely a year as king. Mary was eighteen, widowed, and suddenly without the French future that had been built around her.

She was still a queen—but now she was a queen who had to decide where “home” was.

France had raised her, but Scotland was hers by blood and law. Yet Scotland had changed in her absence. In 1560, Scottish leaders had embraced Protestant reforms and curtailed Catholic influence. Mary, returning as a Catholic monarch to a realm now shaped by Protestant governance, was stepping into a house whose walls had been repainted while she was away.

IV. Homecoming to a Reformed Scotland

In August 1561, Mary sailed back to Scotland. Chroniclers describe a misty arrival—weather that seems almost scripted by history.

She landed with the polish of the French court and the beliefs of a Catholic princess. Scotland greeted her with curiosity, caution, and calculation.

Mary’s first political challenge was religious. Scotland’s Reformation had created a powerful Protestant leadership, including preachers and nobles who believed the nation’s covenant with God depended on rejecting Catholic “idolatry.” At the forefront stood John Knox, whose sermons could ignite a crowd and whose theology left little space for compromise.

Mary, however, attempted something practical: she did not seek to forcibly restore Catholicism across Scotland. Instead, she insisted on the right to practice her faith privately while governing a realm that was, in effect, officially Protestant. She appointed capable administrators and moved with political tact, at least initially. She charmed many with her intelligence and presence, and she demonstrated an ability to listen.

But compromise in a time of religious revolution is rarely stable. Each concession can be interpreted as a threat. Mary’s private Catholic Mass was, to some Protestants, a spark at the edge of a powder magazine. To Catholics, Mary’s restraint could look like weakness or betrayal.

Above all, Mary needed what every monarch needs: stability in succession.

She needed an heir. She needed a marriage.

And in the sixteenth century, the queen’s marriage was never merely personal. It was constitutional. It was international. It was a battlefield in velvet.

V. The Marriage That Changed Everything: Darnley

Mary’s second husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, arrived in Scotland carrying the kind of charm that can be mistaken for destiny. He was handsome, tall, and—critically—he had Tudor blood, strengthening Mary’s claim to the English succession. A marriage to Darnley promised to bolster Mary’s status not only in Scotland but across Europe. To some, it hinted at a future in which Mary might one day sit on England’s throne as well.

But Darnley also carried liabilities like hidden knives. He was ambitious, volatile, and—by many accounts—immature. He wanted power beyond the role of consort. He wanted the crown matrimonial, a title that would grant him sovereign authority alongside Mary.

Mary married Darnley on 29 July 1565. Almost immediately, Scotland’s political temperature rose.

Protestant nobles feared Darnley’s Catholic leanings and the strengthening of Mary’s dynastic claim. Some rebelled. Mary moved decisively and successfully against the uprising, demonstrating that she could still command force and loyalty when needed.

Yet the marriage itself deteriorated with shocking speed. Darnley’s insecurity and appetite for power collided with Mary’s insistence that she alone was the sovereign. Their court became a place of gossip and faction. Darnley’s pride made him malleable to those who wished to manipulate him.

Then came a moment that would stain Mary’s reign and haunt her reputation: the murder of her secretary and confidant, David Rizzio.

VI. Blood on the Floor: Rizzio’s Murder

In March 1566, Mary—pregnant—was dining in a private chamber at Holyrood when conspirators burst in. David Rizzio was seized and stabbed repeatedly. The violence was intimate, meant to terrify. Darnley was implicated in the plot, whether as leader, participant, or pawn.

The murder was not simply a crime of jealousy or personal hatred; it was political theater. Rizzio represented influence—someone close to the queen, perhaps too close for men who wanted to control her decisions. Killing him in her presence was a message: you may wear the crown, but we can still reach into your rooms.

Mary survived the immediate crisis with remarkable composure and cunning. She managed to escape the conspirators’ grip and temporarily reconciled with Darnley, at least enough to maneuver out of danger. In a realm where queens were expected to be either saintly or helpless, Mary demonstrated something else: strategic nerve.

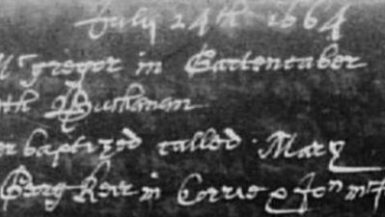

A few months later, on 19 June 1566, Mary gave birth to her only child:

James, born at Edinburgh Castle

He would become James VI of Scotland—and, later, James I of England, uniting the crowns in the next generation.

Mary had secured the succession. But she had not secured peace.

The marriage to Darnley was now a cracked pillar holding up the house of state. And the cracks were widening.

VII. A Child, a Crown, and a Marriage in Ruins

After James’s birth, Darnley’s position worsened. He was increasingly isolated, mistrusted by nobles, and resented by the queen. His desire for authority had not been met; his involvement in Rizzio’s murder made him toxic. He lurched between arrogance and self-pity, seeking allies among those who would use him.

Mary, meanwhile, was a queen in a trap shaped like a marriage. Divorce was politically explosive; separation was precarious; reconciliation seemed impossible.

In this tense atmosphere, another figure rose in prominence: James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell—a powerful nobleman, skilled and bold, with a reputation for ruthlessness and charisma. Bothwell became a key player in Mary’s orbit. Whether he was her protector, her partner, or her future undoing would become one of history’s most contested questions.

In February 1567, Darnley died under circumstances that sounded like a ballad written by a grim poet: his lodging at Kirk o’ Field was destroyed by an explosion, yet Darnley’s body was found outside, suggesting he may have been strangled or otherwise killed after fleeing—or being removed—from the blast.

Suspicion surged like a tide. Many believed Bothwell was involved. Some suspected Mary herself. Others saw a broader conspiracy among nobles who wanted Darnley gone.

Mary’s enemies now held the most dangerous weapon in politics: a narrative.

And within months, Mary’s choices would feed that narrative in ways that proved fatal to her reign.

VIII. The Third Husband: Bothwell and the Point of No Return

In May 1567, Mary married Bothwell.

It is difficult to overstate how catastrophic this looked to the Scottish political class and to foreign observers. Even if Mary had no hand in Darnley’s death, marrying the man widely suspected of orchestrating it seemed like either reckless passion or stunning political miscalculation.

Accounts differ sharply on what led to the marriage. Some later narratives argued that Bothwell abducted Mary and coerced her—possibly through force or assault—into agreement. Others suggest Mary willingly allied with him, seeing in Bothwell a strong partner capable of stabilizing the realm. The truth may be knotted somewhere in between, tangled in a world where a queen’s consent could be simultaneously personal, pressured, and political.

But perception, in the end, mattered more than nuance.

The marriage ignited opposition. Lords rose against Mary and Bothwell, and the conflict culminated at Carberry Hill in June 1567. Mary surrendered—Bothwell fled. And soon, Mary found herself imprisoned at Loch Leven Castle.

There, in one of the most devastating reversals of fortune in royal history, Mary was forced—or persuaded under duress—to abdicate.

Her infant son, James, became king.

Mary, at twenty-four, was a queen without a throne.

IX. Loch Leven: The Queen Becomes a Prisoner

Loch Leven Castle sits in water like a clenched fist. For Mary, it became a place where time thickened. A deposed monarch does not stop being a symbol; she becomes a symbol sharpened by captivity.

She miscarried during her imprisonment—another private grief magnified by political circumstance. She was isolated, watched, and pressed by those who wanted her reign definitively ended.

And then came the “Casket Letters”—documents that her enemies claimed proved Mary’s complicity in Darnley’s murder and demonstrated her passion for Bothwell. The authenticity of these letters has been contested for centuries. Were they genuine? Forged? Altered? Selectively presented? In a time when handwriting could be mimicked and documents weaponized, proof often depended on who held the papers and who controlled the narrative.

What mattered then was that the letters—real or not—gave Mary’s opponents something they could present as moral and political justification for removing her.

Yet Mary did not accept defeat as her natural state.

In May 1568, she escaped Loch Leven—disguised, assisted by allies, moving with the urgency of someone who understands what captivity means. For a brief moment, she reclaimed the role she had been born into: a queen gathering forces.

But at the Battle of Langside, her supporters were defeated. Mary’s options narrowed to a single desperate choice.

She crossed the border into England, seeking protection from her cousin—Elizabeth I.

X. Elizabeth’s Dilemma: A Queen Meets a Queen

If Mary’s life was a tragedy, England was the stage where its final act would be written.

Mary likely believed Elizabeth would help restore her to the Scottish throne—out of kinship, royal solidarity, or political calculation. After all, what monarch wants to validate the idea that nobles can imprison and depose a crowned ruler?

But Elizabeth’s world was shaped by a different fear: Mary was not merely a displaced queen; she was a rival claimant.

To many Catholics, Mary represented a legitimate alternative to Elizabeth—an English throne restored to Catholic alignment through Mary’s bloodline. In an era of religious conflict, Mary’s presence in England was like a lit torch carried into a room full of spilled gunpowder.

Elizabeth faced an agonizing paradox:

- If she helped Mary regain power, she might strengthen a dangerous competitor.

- If she destroyed Mary, she risked establishing the precedent that queens can be tried and executed—an idea that undermined monarchy itself.

So Elizabeth chose a third path: confinement without resolution.

Mary became, effectively, England’s most famous prisoner for nearly nineteen years—moved between castles and manor houses, watched by keepers, living in a suspended state of political limbo.

She remained a queen in title, a symbol in reality, and a problem in perpetuity.

XI. The Long Captivity: Letters, Plots, and the Weight of Waiting

Mary’s imprisonment was not a silent retreat. She corresponded extensively, negotiated through intermediaries, and tried repeatedly to secure her freedom. She appealed to foreign powers. She sought alliances. She tested the cracks in Elizabeth’s court.

Meanwhile, England faced real threats: Catholic powers abroad, internal religious tension, and conspiracies—some real, some exaggerated—aimed at replacing Elizabeth with Mary.

Plots swirled around Mary like moths around a flame: the Ridolfi Plot, the Throckmorton Plot, and later the most consequential of all, the Babington Plot. Whether Mary actively engineered these schemes or was maneuvered into them—or whether her mere existence inspired them—varied from case to case. But the cumulative effect was damning: Mary came to be seen not simply as a prisoner but as a continuing catalyst for rebellion.

Elizabeth’s advisors—especially those focused on security—began to argue that as long as Mary lived, England would never be safe. They pushed for a permanent solution.

Mary, for her part, endured captivity with a queenly insistence on dignity. She maintained her household as best she could. She kept to ceremony. She wrote letters that blended personal longing with political strategy. She cultivated the image of rightful sovereignty, even in confinement.

But prisons shrink the future. They turn plans into daydreams. And they wear down the body while leaving the mind too awake.

By the mid-1580s, the question was no longer whether Mary was dangerous. The question had become whether Elizabeth could afford to keep her alive.

XII. The Trap Closes: Trial and Condemnation

The Babington Plot—a plan involving Elizabeth’s assassination and Mary’s placement on the throne—became the mechanism by which Mary’s enemies secured her downfall. Mary’s correspondence was intercepted and deciphered, and it was presented as evidence that she had sanctioned the scheme.

Mary was brought to trial in 1586. The concept itself was extraordinary: a crowned queen of one realm tried by the authorities of another. Mary argued that, as a sovereign, she was not subject to English law. She had come to England seeking aid, not judgment. She protested that she was being denied the full rights of defense.

But the outcome was increasingly inevitable. Politics had already made its decision; the trial’s role was to provide the formal language that allowed action.

Mary was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Elizabeth hesitated—whether from conscience, fear of precedent, or fear of retaliation from Catholic Europe. But hesitation in politics is often only a pause before the wheel turns. Her advisors pressed. Parliament urged. The logic of security—cold, numerical, unforgiving—tightened around the queen’s neck.

A warrant was signed.

And Mary was moved toward her end.

XIII. Fotheringhay: The Last Morning of a Queen

Mary’s execution took place at Fotheringhay Castle on 8 February 1587.

In her final days, Mary prepared with the precision of someone who understood she was stepping into history. She dressed with symbolic care—reportedly in colors associated with martyrdom—transforming the scaffold into a stage where she could claim the meaning of her death.

She met the end with courage that even opponents could not easily dismiss. Witness accounts emphasize her composure, her prayers, her insistence on her identity as a queen and as a Catholic.

Execution is always brutal, no matter how ceremonial. It is the state’s final argument, delivered in steel.

And when it was done, the political world shifted. Elizabeth would later claim distress and anger that the execution had been carried out—suggesting distance between her signature and the axe. Whether that was genuine regret, political theater, or both, history can only weigh.

But the fact remained: a queen had been executed under another queen’s authority.

Europe took note.

So did time.

XIV. Husbands, Children, and the Dynasty That Outlived Tragedy

Mary’s personal life is inseparable from her political fate. Her marriages were not just romances; they were alliances and detonations.

Husband #1: Francis II of France

- Mary married Francis in 1558.

- She became Queen Consort of France in 1559.

- Francis died in 1560, leaving Mary widowed at eighteen.

- The marriage connected Mary to the high politics of Catholic Europe and intensified fears in England about her claim.

Husband #2: Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

- Married in 1565.

- Their union strengthened Mary’s claim to the English throne.

- The marriage collapsed into faction and scandal.

- Darnley was implicated in Rizzio’s murder and later died in 1567 under suspicious circumstances.

Husband #3: James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

- Married in 1567.

- The marriage was viewed as a political catastrophe due to suspicion around Darnley’s death.

- It triggered rebellion and led directly to Mary’s deposition.

Child: James VI of Scotland (later James I of England)

Mary had one child, James, born in 1566.

This fact—simple and enormous—became Mary’s most enduring legacy.

James grew up largely separated from his mother, raised amid the Protestant politics that had overthrown her. He inherited a Scottish throne shaped by compromise and constraint. And in 1603, after Elizabeth I died without children, James inherited the English throne as well, becoming James I of England, and thus uniting the crowns of Scotland and England in one person.

In a strange twist of history’s humor, Mary’s claim—so feared during her life—became the very pathway by which the Stuart line achieved what Mary never could: rule across both kingdoms.

The mother died on a scaffold; the son became king of a larger realm than she had ever held.

XV. The Afterlife of a Reputation

Mary’s story has never stayed settled. She is one of those historical figures who seems to change shape depending on who is looking.

- To some, she is a Catholic martyr—faithful unto death.

- To others, she is a romantic tragic heroine—undone by love and betrayal.

- To some, she is a politically naïve queen whose choices accelerated her downfall.

- To others, she is a woman boxed in by constraints her male counterparts never faced: a queen expected to marry for politics, yet punished when her marriages became political disasters.

What is clear is that Mary lived at the intersection of forces that were larger than any one person:

- the Reformation and counter-Reformation,

- the struggle between England and Scotland,

- the shifting architecture of monarchy,

- and the question of whether sovereign power could survive in an age of ideological war.

Mary’s life also exposes a harsh truth: the personal is never merely personal when you wear a crown. Every affection becomes policy. Every quarrel becomes faction. Every child becomes a diplomatic event. A queen can be judged not only by her acts, but by the acts others commit in her name.

On anniversaries, we can feel both the ache and the lesson.

Mary’s tragedy was not that she loved too much or ruled too poorly—though one can argue the missteps. Her tragedy was that she lived in an age where a queen’s body was a contested territory: her marriage bed a treaty table, her fertility a national security issue, her faith a political weapon, her claim a threat.

And in the end, her death was not simply punishment. It was a solution to someone else’s fear.

XVI. The Anniversary’s Quiet Question

So what do we do with Mary, Queen of Scots, when the calendar returns to her beginnings and her end?

We remember that history is not only the march of parliaments and armies; it is also the fragile continuity of a human life pressed between obligation and desire. We remember the young girl who left Scotland for France, the queen who returned to find her realm transformed, the mother who kissed her infant son knowing the world might take him away, the prisoner who wrote letters by candlelight, the condemned woman who refused to let the scaffold steal her dignity.

And we remember, too, the unsettling symmetry:

Mary’s execution was meant to end a problem.

Instead, it ensured her immortality.

Time has a way of granting the last word to those who lost the argument in their own century.

On this anniversary, Mary stands again in the corridor of doors—queen, widow, mother, prisoner, claimant, symbol. And if we listen carefully, we can hear what she leaves behind, not as a slogan but as a warning written in lived experience:

A crown is never only gold.

Sometimes it is a weight.

Sometimes it is a sentence.

And sometimes—most haunting of all—it is both.