Approximately 40 wildland firefighters continue to fight off the 24-acre Kolob Terrace Fire, in Hop Valley, Zion National Park. https://www.nps.gov/zion/learn/news/update-wildland-firefighters-continue-to-address-kolob-terrace-fire.htm

One of the things that I love most about cross country road trips is that you end up discovering areas of the country that you had never thought about. So when Saydie and I decided that we would head north to the Black Hills from Zion National Park, this was an awesome opportunity to plan our route through parts of the United States that I had never driven through before, so this new for both Saydie and I. One such location was Thunder Basin National Grassland which is located north east of Casper, Wyoming.

I am familiar with National Grasslands, as I travel through the National Tall Grass Prairie in Kansas pretty regular when I am staying up in Merriam. But this is the first time I was traveling through Thunder Basin.

One of the things that always amazes me, when I find myself in locations such as what is pictured above. I find myself imagining all the man made things not being there, such as the fences, the road, anything modern. I find myself thinking of me, traveling on horse back in this place and wondering what it would be like.

As Saydie and I were traveling I noticed a sign that informed us that we were traveling through four National Historic trails which I thought was pretty cool.

The sign said we were traveling through the Oregon Trail, the California Trail, the Mormon Pioneer Trail and the Pony Express. All very important trails that played key roles in the expansion west in the United States.

The Oregon Trail, is a 2,170-mile (3,490 km) and it is an historic east-west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of the future state of Kansas, and nearly all of what are now the states of Nebraska and Wyoming. The western half of the trail spanned most of the future states of Idaho and Oregon.

The Oregon Trail was laid by fur traders and trappers from about 1811 to 1840, and was only passable on foot or by horseback. By 1836, when the first migrant wagon train was organized in Independence, Missouri, a wagon trail had been cleared to Fort Hall, Idaho. Wagon trails were cleared increasingly farther west, and eventually reached all the way to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, at which point what came to be called the Oregon Trail was complete, even as almost annual improvements were made in the form of bridges, cutoffs, ferries, and roads, which made the trip faster and safer. From various starting points in Iowa, Missouri, or Nebraska Territory, the routes converged along the lower Platte River Valley near Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory, and led to rich farmlands west of the Rocky Mountains.

From the early to mid-1830s (and particularly through the years 1846–1869) the Oregon Trail and its many offshoots were used by about 400,000 settlers, farmers, miners, ranchers, and business owners and their families. The eastern half of the trail was also used by travelers on the California Trail (from 1843), Mormon Trail (from 1847), and Bozeman Trail (from 1863), before turning off to their separate destinations. Use of the trail declined as the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, making the trip west substantially faster, cheaper, and safer. Today, modern highways, such as Interstate 80 and Interstate 84, follow parts of the same course westward and pass through towns originally established to serve those using the Oregon Trail.

The California Trail was an emigrant trail of about 3,000 miles across the western half of the North American continent from the Missouri River towns to what is now the state of California.

By 1847, two former fur trading frontier forts marked trailheads for major alternative routes through Utah and Wyoming to Northern California. The first was Jim Bridger’s Fort Bridger (est. 1842) in present-day Wyoming on the Green River, where the Mormon Trail turned southwest over the Wasatch Range to the newly established Salt Lake City, Utah. From Salt Lake the Salt Lake Cutoff (est. 1848) went north and west of the Great Salt Lake and rejoined the California Trail in the City of Rocks in present-day Idaho.

The main Oregon and California Trails crossed the Yellow River on several different ferries and trails (cutoffs) that led to or bypassed Fort Bridger and then crossed over a range of hills to the Great Basin drainage of the Bear River (Great Salt Lake). Just past present-day Soda Springs, Idaho, both trails initially turned northwest, following the Portneuf River (Idaho) valley to the British Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Hall (est. 1836) on the Snake River in present-day Idaho. From Fort Hall the Oregon and California trails went about 50 miles (80 km) southwest along the Snake River Valley to another “parting of the ways” trail junction at the junction of the Raft and Snake rivers. The California Trail from the junction followed the Raft River to the City of Rocks in Idaho near the present Nevada-Idaho-Utah tripoint. The Salt Lake and Fort Hall routes were about the same length: about 190 miles (310 km).

From the City of Rocks the trail went into the present state of Utah following the South Fork of the Junction Creek. From there the trail followed along a series of small streams, such as Thousand Springs Creek in the present state of Nevada until approaching present-day Wells, Nevada, where they met the Humboldt River. By following the crooked, meandering Humboldt River Valley west across the arid Great Basin, emigrants were able to get the water, grass, and wood they needed for themselves and their teams. The water turned increasingly alkaline as they progressed down the Humboldt, and there were almost no trees. “Firewood” usually consisted of broken brush, and the grass was sparse and dried out. Few travelers liked the Humboldt River Valley passage.

[The] Humboldt is not good for man nor beast … and there is not timber enough in three hundred miles of its desolate valley to make a snuff-box, or sufficient vegetation along its banks to shade a rabbit, while its waters contain the alkali to make soap for a nation.

— Reuben Cole Shaw, 1849

At the end of the Humboldt River, where it disappeared into the alkaline Humboldt Sink, travelers had to cross the deadly Forty Mile Desert before finding either the Truckee River or Carson Riverin the Carson Range and Sierra Nevada mountains that were the last major obstacles before entering Northern California.

An alternative route across the present states of Utah and Nevada that bypassed both Fort Hall and the Humboldt River trails was developed in 1859. This route, the Central Overland Route, which was about 280 miles (450 km) shorter and more than 10 days quicker, went south of the Great Salt Lake and across the middle of present-day Utah and Nevada through a series of springs and small streams. The route went south from Salt Lake City across the Jordan River to Fairfield, Utah, then west-southwest past Fish Springs National Wildlife Refuge, Callao, Utah, Ibapah, Utah, to Ely, Nevada, then across Nevada to Carson City, Nevada. (Today’s U.S. Route 50 in Nevada roughly follows this route.) (See: Pony Express Map) In addition to immigrants and migrants from the East, after 1859 the Pony Express, Overland stages and the First Transcontinental Telegraph (1861) all followed this route with minor deviations.

Once in western Nevada and eastern California, the pioneers worked out several paths over the rugged Carson Range and Sierra Nevada mountains into the gold fields, settlements and cities of northern California. The main routes initially (1846–48) were the Truckee Trail to the Sacramento Valley and after about 1849 the Carson Trail route to the American River and the Placerville, California gold digging region.

Starting about 1859 the Johnson Cutoff (Placerville Route, est. 1850–51) and the Henness Pass Route (est. 1853) across the Sierra were greatly improved and developed. These main roads across the Sierra were both toll roads so there were funds to pay for maintenance and upkeep on the roads. These toll roads were also used to carry cargo west to east from California to Nevada, as thousands of tons of supplies were needed by the gold and silver miners, etc. working on the Comstock Lode (1859–88) near the present Virginia City, Nevada. The Johnson Cutoff, from Placerville to Carson City along today’s U.S. Route 50 in California, was used by the Pony Express (1860–61) year-round and in the summer by the stage lines (1860–69). It was the only overland route from the East to California that could be kept partially open for at least horse traffic in the winter.

The California Trail was heavily used from 1845 until several years after the end of the American Civil War; in 1869 several rugged wagon routes were established across the Carson Range and Sierra Nevada mountains to different parts of northern California. After about 1848 the most popular route was the Carson Route which, while rugged, was still easier than most others and entered California in the middle of the gold fields. The trail was heavily used in the summers until the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 by the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads. Trail traffic rapidly fell off as the cross-country trip was much quicker and easier by train—about seven days. The economy class fare across the western United States of about $69 was affordable by most California-bound travelers.

The trail was used by about 2,700 settlers from 1846 up to 1849. These settlers were instrumental in helping convert California to a U.S. possession. Volunteer members of John C. Frémont’s California Battalion assisted the Pacific Squadron’s sailors and marines in 1846 and 1847 in conquering California in the Mexican–American War. After the discovery of gold in January 1848, word spread about the California Gold Rush. Starting in late 1848 till 1869, more than 250,000 businessmen, farmers, pioneers and miners passed over the California Trail to California. The traffic was so heavy that in two years the new settlers added so many people to California that by 1850 it qualified for admission as the 31st state with 120,000 residents. The Trail travelers were added to those migrants going by wagon from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles, California in winter, the travelers down the Gila River trail in Arizona, and those traveling by sea routes around Cape Horn and the Strait of Magellan, or by sea and then across the Isthmus of Panama, Nicaragua or Mexico, and then by sea to California. Roughly half of California’s new settlers came by trail and the other half by sea.

The original route had many branches and cutoffs, encompassing about 5,500 miles (8,900 km) in total. About 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of the rutted traces of these trails remain in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada and California as historical evidence of the great mass migration westward. Portions of the trail are now preserved by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the National Park Service (NPS) as the California National Historic Trail and marked by BLM, NPS and the many state organizations of the Oregon-California Trails Association (OCTA). Maps put out by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) show the network of rivers followed to get to California.

Establishment (1811–1840)

The beginnings of the California and Oregon Trails were laid out by mountain men and fur traders from about 1811 to 1840 and were only passable initially on foot or by horseback. South Pass, the easiest pass over the U.S. continental divide of the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean drainages, was discovered by Robert Stuart and his party of seven in 1812 while he was taking a message from the west to the east back to John Jacob Astor about the need for a new ship to supply Fort Astoria on the Columbia River—their supply ship Tonquin had blown up. In 1824, fur traders/trappers Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick rediscovered the South Pass as well as the Sweetwater, North Platte and Platte River valleys connecting to the Missouri River.

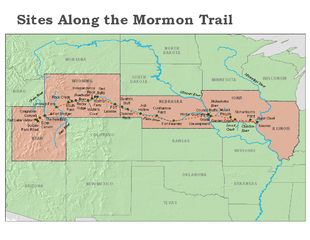

Mormon Pioneer Trail

The Mormon Trail is the 1,300-mile (2,100 km) long route from Illinois to Utah that members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traveled for 3 months. Today, the Mormon Trail is a part of the United States National Trails System, known as the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail.

The Mormon Trail extends from Nauvoo, Illinois, which was the principal settlement of the Latter Day Saints from 1839 to 1846, to Salt Lake City, Utah, which was settled by Brigham Young and his followers beginning in 1847. From Council Bluffs, Iowa to Fort Bridger in Wyoming, the trail follows much the same route as the Oregon Trail and the California Trail; these trails are collectively known as the Emigrant Trail.

The Mormon pioneer run began in 1846, when Young and his followers were driven from Nauvoo. After leaving, they aimed to establish a new home for the church in the Great Basin and crossed Iowa. Along their way, some were assigned to establish settlements and to plant and harvest crops for later emigrants. During the winter of 1846–47, the emigrants wintered in Iowa, other nearby states, and the unorganized territory that later became Nebraska, with the largest group residing in Winter Quarters, Nebraska. In the spring of 1847, Young led the vanguard company to the Salt Lake Valley, which was then outside the boundaries of the United States and later became Utah.

During the first few years, the emigrants were mostly former occupants of Nauvoo who were following Young to Utah. Later, the emigrants increasingly included converts from the British Isles and Europe.

The trail was used for more than 20 years, until the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Among the emigrants were the Mormon handcart pioneers of 1856–60. Two of the handcart companies, led by James G. Willie and Edward Martin, met disaster on the trail when they departed late and were caught by heavy snowstorms in Wyoming.

All but two of the handcart companies successfully completed the rugged journey, with relatively few problems and only a few deaths. However, the fourth and fifth companies, known as the Willie and Martin Companies, respectively, had serious problems. The companies left Iowa City, Iowa, in July 1856, very late to begin the trip across the plains. They met severe winter weather west of present-day Casper, Wyoming, and continued to cope with deep snow and storms for the remainder of the journey. Food supplies were soon exhausted. Young organized a rescue effort that brought the companies in, but more than 210 of the 980 emigrants in the two parties died.

The handcart companies continued with more success until 1860, and traditional ox-and-wagon companies also continued for those who could afford the higher cost. After 1860, the church began sending wagon companies east each spring, to return to Utah in the summer with the emigrating Latter-day Saints. Finally, with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, future emigrants were able to travel by rail, and the era of the Mormon pioneer trail came to an end.

Pony Express

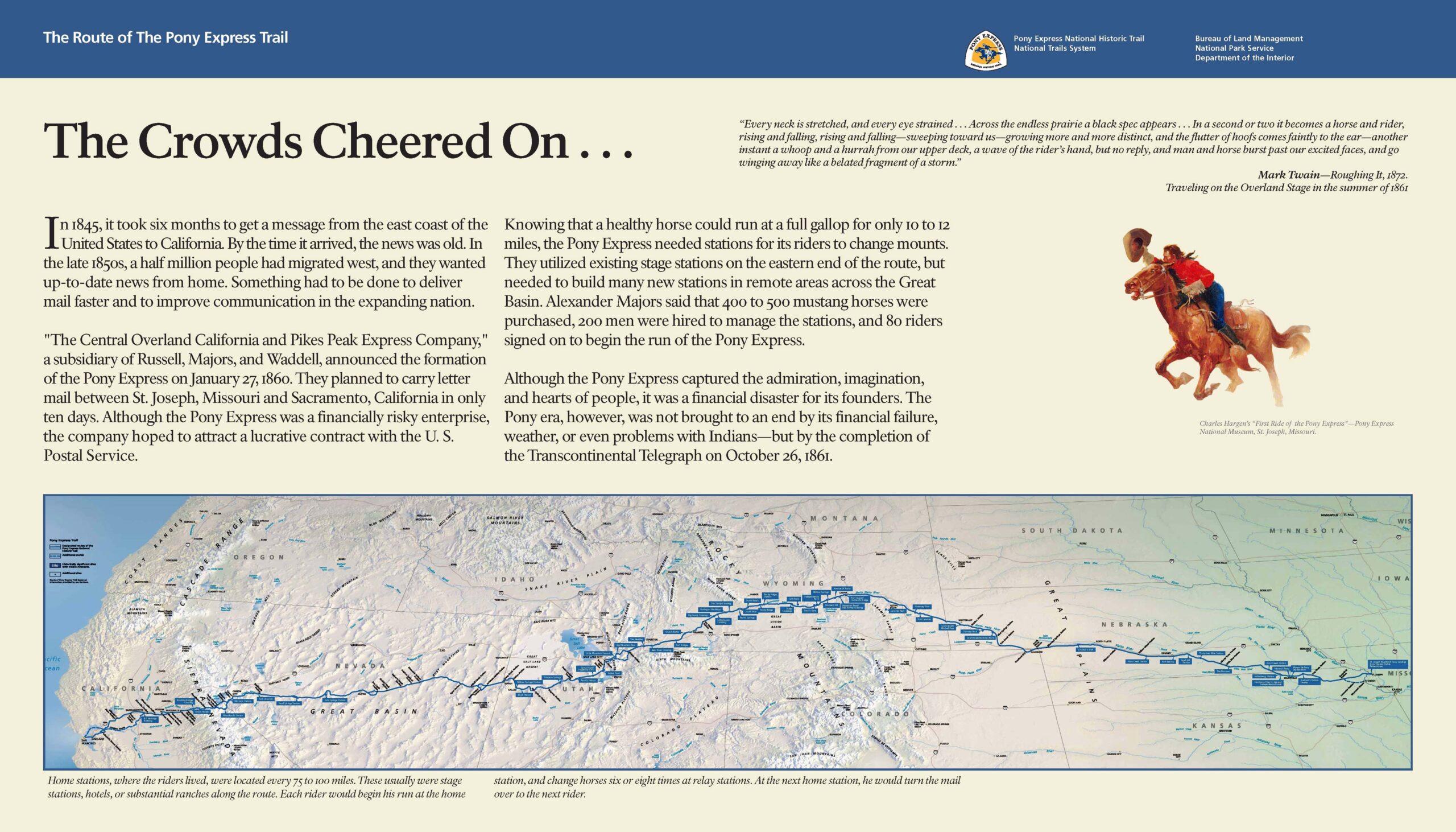

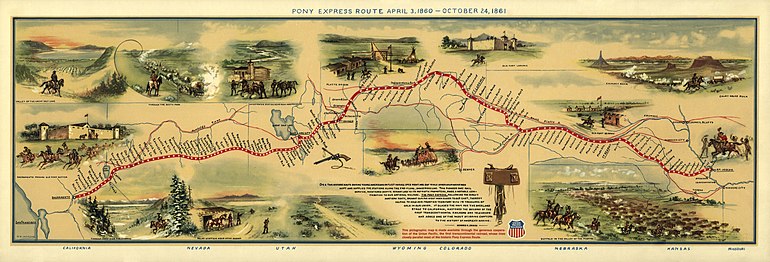

The Pony Express was a mail service delivering messages, newspapers, and mail using relays of horse-mounted riders that operated from April 3, 1860, to October 24, 1861, between Missouri and California in the United States of America.

The approximately 1,900-mile-long (3,100 km) route roughly followed the Oregon and California Trails to Fort Bridger in Wyoming, and then the Mormon Trail (known as the Hastings Cutoff) to Salt Lake City, Utah. From there, it followed the Central Nevada Route to Carson City, Nevada Territory, before passing over the Sierra into Sacramento, California.

The route started at St. Joseph, Missouri, on the Missouri River, and then followed what is modern-day U.S. Highway 36 (the Pony Express Highway) to Marysville, Kansas, where it turned northwest following Little Blue River to Fort Kearny in Nebraska. Through Nebraska, it followed the Great Platte River Road, cutting through Gothenburg, Nebraska, clipping the edge of Colorado at Julesburg, Colorado, and passing Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff, before arriving first at Fort Laramie and then Fort Caspar (Platte Bridge Station) in Wyoming. From there, it followed the Sweetwater River, passing Independence Rock, Devil’s Gate, and Split Rock, through South Pass to Fort Bridger and then south to Salt Lake City. From Salt Lake City, it generally followed the Central Nevada Route blazed by Captain James H. Simpson of the Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1859. This route roughly follows today’s US 50 across Nevada and Utah. It crossed the Great Basin, the Utah-Nevada Desert, and the Sierra Nevada near Lake Tahoe before arriving in Sacramento. Mail was then sent by steamer down the Sacramento River to San Francisco. On a few instances when the steamer was missed, riders took the mail by horseback to Oakland, California.

Famous riders

In 1860, riding for the Pony Express was difficult work – riders had to be tough and lightweight. A famous advertisement allegedly read:

Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred

The Pony Express had an estimated 80 riders traveling east or west along the route at any given time. In addition, about 400 other employees were used, including station keepers, stock tenders, and route superintendents. Many young men applied; Waddell and Majors could have easily hired riders at low rates, but instead offered $100 a month – a handsome sum for that time. Author Mark Twain described the riders in his travel memoir Roughing It as: “… usually a little bit of a man”. Though the riders were small, lightweight, generally teenaged boys, they came to be seen as heroes of the American West. There was no systematic list of riders kept by the company, but a partial list has been compiled by Raymond and Nancy Settle in their Saddles & Spurs (1972).

First riders

The identity of the first westbound rider to depart St. Joseph has been disputed, but currently most historians have narrowed it down to either Johnny Fry or Billy Richardson. Both Expressmen were hired at St. Joseph for A. E. Lewis’ Division, which ran from St. Joseph to Seneca, Kansas, a distance of 80 miles (130 km). They covered at an average speed of 12 1⁄2miles per hour (20 km/h), including all stops. Before the mail pouch was delivered to the first rider on April 3, 1860, time was taken out for ceremonies and several speeches. First, Mayor M. Jeff Thompson gave a brief speech on the significance of the event for St. Joseph. Then William H. Russell and Alexander Majors addressed the gala crowd about how the Pony Express was just a “precursor” to the construction of a transcontinental railroad. At the conclusion of all the speeches, around 7:15 pm, Russell turned the mail pouch over to the first rider. A cannon fired, the large assembled crowd cheered, and the rider dashed to the landing at the foot of Jules Street,where the ferry boat Denver, under a full head of steam, alerted by the signal cannon, waited to carry the horse and rider across the Missouri River to Elwood, Kansas Territory. On April 9 at 6:45 pm, the first rider from the east reached Salt Lake City, Utah. Then, on April 12, the mail pouch reached Carson City, Nevada Territory, at 2:30 pm. The riders raced over the Sierra Nevadas, through Placerville, California, and on to Sacramento. Around midnight on April 14, 1860, the first mail pouch was delivered by the Pony Express to San Francisco. With it was a letter of congratulations from President Buchanan to California Governor Downey along with other official government communications, newspapers from New York, Chicago, and St. Louis, and other important mail to banks and commercial houses in San Francisco. In all, 85 pieces of mail were delivered on this first trip.

James Randall is credited as “the first eastbound rider” from the San Francisco Alta telegraph office, since he was on the steamship Antelope to go to Sacramento. Mail for the Pony Express left San Francisco at 4:00 pm, carried by horse and rider to the waterfront, and then on by steamboat to Sacramento, where it was picked up by the Pony Express rider. At 2:45 am, William (Sam) Hamilton was the first Pony Express rider to begin the journey from Sacramento. He rode all the way to Sportsman Hall Station, where he gave his mochila filled with mail to Warren Upson. A California Registered Historical Landmark plaque at the site reads:

This was the site of Sportsman’s Hall, also known as the Twelve-Mile House. The hotel operated in the late 1850s and 1860s by John and James Blair. A stopping place for stages and teams of the Comstock, it became a relay station of the central overland Pony Express. Here, at 7:40 am, April 4, 1860, Pony rider William (Sam) Hamilton, riding in from Placerville, handed the Express mail to Warren Upson who, two minutes later, sped on his way eastward.

— Plaque at Sportsman Hall

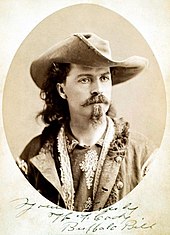

William Cody

Probably more than any other rider in the Pony Express, William Cody (better

known as Buffalo Bill) epitomizes the legend and the folklore, be it fact or fiction, of the Pony Express. Numerous stories have been told of young Cody’s adventures as a Pony Express rider. At the age of 15, Cody was on his way west to California when he met Pony Express agents along the way and signed on with the company. Cody helped in the construction of several way-stations. Thereafter, he was employed as a rider and was given a short 45-mile (72 km) delivery run from the township of Julesburg, which lay to the west. After some months, he was transferred to Slade’s Division in Wyoming, where he made the longest nonstop ride from Red Buttes Station to Rocky Ridge Station and back when he found that his relief rider had been killed. The distance of 322 miles (518 km) over one of the most dangerous sections of the entire trail was completed in 21 hours and 40 minutes, and 21 horses were required to complete this section. On one occasion when carrying mail, he unintentionally ran into an Indian war party, but managed to escape. Cody was present for many significant chapters in early western history, including the gold rush, the building of the railroads, and cattle herding on the Great Plains. A career as a scout for the Army under General Phillip Sheridan following the Civil War earned him his nickname and established his notoriety as a frontiersman.

Closing

During its brief time in operation, the Pony Express delivered about 35,000 letters between St. Joseph and Sacramento. Although the Pony Express proved that the central/northern mail route was viable, Russell, Majors, and Waddell did not get the contract to deliver mail over the route. The contract was instead awarded to Jeremy Dehut in March 1861, who had taken over the southern, congressionally favored Butterfield Overland Mail Stage Line. The so-called “Stagecoach King”, Ben Holladay, acquired the Russell, Majors, and Waddell stations for his stagecoaches.

Shortly after the contract was awarded, the start of the American Civil War caused the stage line to cease operation. From March 1861, the Pony Express ran mail only between Salt Lake City and Sacramento. The Pony Express announced its closure on October 26, 1861, two days after the transcontinental telegraph reached Salt Lake City and connected Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento. Other telegraph lines connected points along the line and other cities on the east and west coasts.

Despite the subsidy, the Pony Express was a financial failure. It grossed $90,000 and lost $200,000.

In 1866, after the Civil War was over, Holladay sold the Pony Express assets along with the remnants of the Butterfield Stage to Wells Fargo for $1.5 million.